Alan Shepard became the first American to reach space when he launched on a suborbital flight on May 5, 1961.

Shepard narrowly missed out on being the first human in space -- Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin beat him to the punch about three weeks earlier, successfully completing one orbit of Earth on April 12.

To mark the 50th anniversary of Shepard's flight, here are answers to a few basic questions about his historic mission, which ushered in the age of American human spaceflight. [Photos: America's 1st Human Spaceflight]

How high did Alan Shepard fly?

Shepard's achievement was much more modest than that of Gagarin, who reached Earth orbit and stayed aloft for 108 minutes.

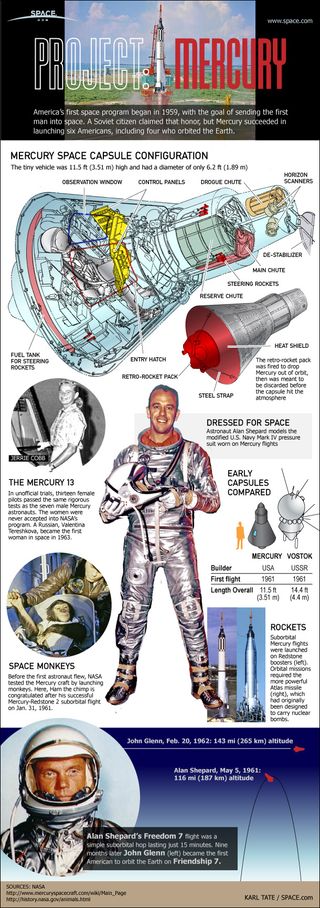

Shepard's Mercury spacecraft -- which bore the name Freedom 7 -- made it to suborbital space, reaching a peak altitude of 116 miles (187 kilometers) and a top speed of 5,180 mph (8,336 km). The flight lasted just 15 minutes before splashing down in the Atlantic Ocean 302 miles (486 km) from the Florida launch site. [Infographic: Mercury - America's First Spaceship]

The U.S. wouldn't duplicate Gagarin's feat for nearly a year, until John Glenn's orbital flight in February 1962.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

How big was Shepard's Freedom 7 spaceship?

Shepard was packed pretty tightly into the one-man Freedom 7 capsule, which measured 11.5 feet (3.5 meters) tall and was just 6.2 feet (1.9 m) across at its widest point. By contrast, Gagarin's Vostok 1 capsule was about 14.4 feet (4.4 m) high.

The Freedom 7 wasn't built for comfort or sightseeing. It had portholes instead of windows, and Shepard made his key Earth observations through a periscope, like a submarine captain. [Giant Leaps: Top Milestones in Human Spaceflight]

Still, the astronaut managed to make out some landmarks on terra firma during his flight. He spotted Florida's Lake Okeechobee, as well as some islands in the Bahamas, according to NASA officials.

A Redstone booster lofted the Freedom 7 to suborbital space. When NASA initiated orbital flights in 1962, the agency employed more powerful Atlas rockets, which had originally been designed to carry nuclear bombs.

Did Shepard actually fly the Freedom 7, or was he just human cargo?

Gagarin's flight was largely automated, so the cosmonaut didn't have to do much during his orbital sojourn. But Shepard played a more active role on his maiden spaceflight, taking control of the Freedom 7 for several brief periods.

For example, Shepard manually positioned the capsule to fire its retrorockets, which helped the craft decelerate. He also corrected a slight pitch problem in one instance, and he steered the craft by hand for a spell during re-entry, according to NASA officials.

Could Shepard have beaten Gagarin to space?

Historians say Shepard's flight likely could have occurred before April 12, 1961, if NASA and chief rocket designer Wernher von Braun had been a little less cautious.

On Dec. 19, 1960, NASA launched an unmanned Mercury capsule atop a Redstone booster into suborbital space for the first time. That test flight was a success, so the agency soon ramped up to a "semi-manned" test, launching a chimp named Ham into suborbital space on Jan. 31, 1961.

Though Ham came through his space jaunt unscathed, some problems with the Redstone emerged during the flight. This concerned NASA and von Braun, especially since a Redstone test flight in November 1960 had failed, getting only 4 inches (10 centimeters) off the pad.

So, late in the game, von Braun and the space agency decided to insert one more unmanned test flight into the Mercury project's schedule. This flight took place on March 24, and everything worked well, clearing the way for Shepard's manned mission. [Most Extreme Human Spaceflight Records]

The extra test flight was intended to make sure NASA had worked out all the Redstone's kinks before risking Shepard's life. But the delay opened a window of opportunity for the Soviets, and they leapt through it, launching Gagarin on April 12.

Shepard himself seemed to think NASA's caution was unwarranted, or at least unfortunate.

"We had 'em," Shepard is reported to have said at the time, referring to the Soviets. "We had 'em by the short hairs, and we gave it away."

Did it matter that Gagarin was first?

Gagarin's flight was the second major victory for the Soviet Union in its Cold War space race with the U.S. The first was the surprise launch of Sputnik I, the world's first articial satellite, in October 1957.

While Gagarin and Sputnik bruised American pride, they spurred the nation's space program to new heights. Without those twin shocks, historians say, the Apollo program – an all-out rush to the moon designed to firmly establish American space supremacy – would likely never have been possible.

"A lot of these factors had to line up -- Sputnik, Gagarin, all this stuff," space historian Asif Siddiqi of Fordham University, told SPACE.com last month. "That kind of crash mentality is not there anymore, because we haven't had that kind of a shock since then."

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.