Mercury Mystery Solved: Scientists Decode Planet's Weird Surface

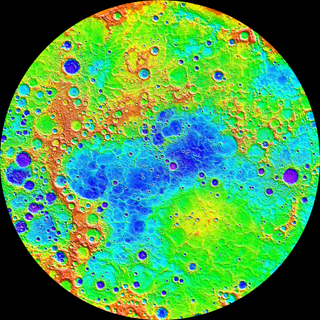

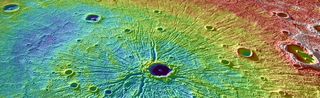

Mercury has a very diverse surface, with some areas boasting young-looking terrain and others that are heavily cratered, but scientists couldn't explain why the planet's surface had such stark differences — until now.

Mercury's Northern Volcanic Plains, for example, appear to have formed more recently than other parts of the planet, likely due to tectonic activity that shifted the ground. The planet's intercrater plains, however, are heavily cratered, suggesting that the terrain in that area is older, according to a NASA statement.

Using data from NASA's MESSENGER spacecraft — which orbited Mercury from 2011 to 2015 — scientists at the Johnson Space Center took a closer look at how a mix of young and old terrain could develop. [Photos of Mercury from NASA's Messenger Probe]

"We think that planets start hot and almost completely melt," Asmaa Boujibar, NASA postdoctoral fellow and lead author of the study, said in the statement. "As they cool, they crystallize various minerals. In some cases, minerals can separate to form different layers inside the planets."

Evidence of this type of layering process has been observed in samples brought back from the moon during Apollo missions. However, this is far different than any process seen on Earth.

"Earth does not seem to have these layers, either because the minerals never separated, or because the movement of its surface plates, called tectonics, has mixed everything up again," Boujibar added.

The researchers simulated what Mercury's interior might be like to try to work out the cause of the vast differences seen on the planet's surface. The researchers wanted to see if Mercury's interior has chemical layers like the moon, or is evenly mixed and homogenous like Earth.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To simulate Mercury's interior, the researchers subjected enstatite chondrites — a type of meteorite that researchers think could be closest to Mercury's building blocks — to the high temperatures and pressures found deep inside the planet.

The researchers found that Mercury wouldn't need those layers — a homogenous interior, all with the same composition, could have created the observed old and new terrain. Older terrains likely formed from material that was transported to the planet's surface from deep inside its interior, which would have been subjected to increased pressure and heat, the researchers said. The younger terrain, on the other hand, likely formed from material that started out closer to the planet's surface, which was under less temperature and pressure stress, they added.

"The key finding is that by varying pressure and temperature on only one type of composition, we could produce the variety of material found on the planet's surface," Boujibar said.

Next, the researchers hope to learn more about Mercury's interior and when it became homogenous. Future studies will look at whether the planet experienced convection processes early in its history, which would have mixed everything up, or whether it never had chemical layers to begin with.

This research has vast implications for better understanding how the solar system formed, NASA officials said — if Mercury really formed from the studied materials, it would mean Earth, the moon and Mercury all had similar compositions, suggesting that the inner solar system could be made all of the same material rather than many different materials.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.