Five Floating Facts for the 50th Anniversary of the 1st American Spacewalk

Ed White may not have been the first man to walk in space, but his extravehicular activity, or EVA, 50 years ago Wednesday (June 3) was no less historic.

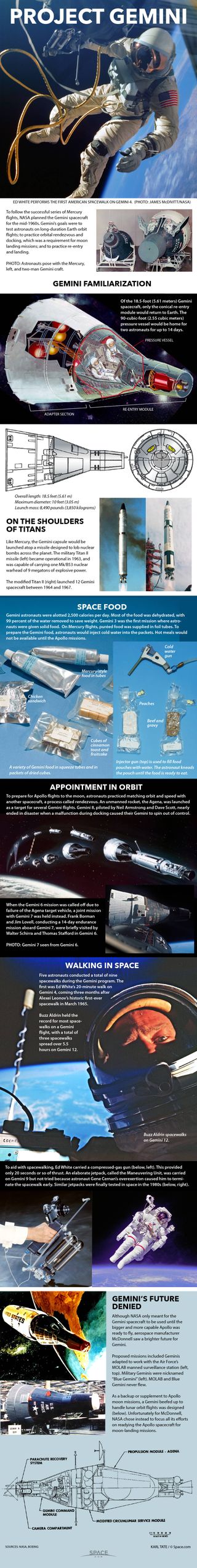

The first U.S. astronaut to exit a spacecraft while in orbit, White spent more than 20 minutes floating in the vacuum of space, protected only by a spacesuit. He moved about using a "zip gun," a hand-held maneuvering unit, while still attached to Gemini 4 by a tether and umbilical.

"I feel like a million dollars!" White exclaimed to his crewmate James McDivitt, who was snapping photos from his seat on the spacecraft. That excitement lasted until White was ordered back inside by Mission Control. [The 1st American Spacewalk in Photos]

"I'm coming back in... and it's the saddest moment of my life," White radioed.

Paired with his predecessor, Soviet-era cosmonaut Alexei Leonov, the two were written into the history books as the world's first spacewalkers. But there was more to White's walk than the floating feat alone.

"Gemini 4, Houston"

Half a century later, mention of "Mission Control," usually brings to mind Houston. But it wasn't always that way. For all of NASA's Mercury missions and its first Gemini flight, the ground controllers were located near the launch site at Cape Canaveral in Florida.

"The Gemini 4 mission marks the first time that mission control will be exercised at the Manned Spacecraft Center, Houston," NASA's 1965 press kit for the Gemini 4 mission stated, referring to the center that eight years later would be renamed the Johnson Space Center.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

With flight director Christopher C. Kraft leading the room, it fell to Gemini 3 commander and original Mercury astronaut Virgil "Gus" Grissom to deliver the first words spoken from Houston to a manned spacecraft.

"Gemini 4, Houston Cap Com," Grissom, as the mission's capsule communicator, radioed 2 minutes and 10 seconds into the flight. At the time, the Titan rocket that was lofting Gemini 4 into space was ready for first stage separation. [Video: NASA Astronaut Recounts 50 Years of Spacewalks]

Patriotic patch

Visit any NASA center or museum gift shop and you will likely find a red and white embroidered patch depicting an astronaut on an EVA and the words "Gemini 4 First Space Walk." Neither McDivitt nor White had anything to do with this souvenir design.

NASA's first crew-created mission patch came on the next mission, Gemini 5. The Gemini 4 crew set a different first.

"Ed White and I used the American flag on our shoulders as our patch," McDivitt said, according to Dick Lattimer in the book, "All We Did Was Fly to the Moon."

Gemini 4 marked the first time that the U.S. flag had been worn on a spacesuit, a tradition continued ever since, said McDivitt. Later flags were embroidered; the Gemini 4 flags were made of nylon.

"The flags we had sewn on we purchased ourselves," the Gemini 4 commander recalled. "Later on, of course, NASA made this an integral part of the pressure suit."

A more traditional Gemini 4 patch, based on the design of the crew's American eagle-adorned medallions, was made with McDivitt's endorsement decades later. (White died in 1967 in the Apollo 1 pad fire.)

Seedy souvenir

Both McDivitt and White had small pouches packed with mementos on Gemini 4. The two flew silver medallions (of the aforementioned American eagle design) and state and international flags, among other trinkets, to gift to friends, family and supporters after the mission was over.

All of the souvenirs remained inside the capsule, with the exception of a small stash of seeds.

As he was walking in space, White carried mustard seeds in his spacesuit's pocket. The seeds were a symbol of his religion, in reference to the New Testament's description of Jesus using the mustard seed as a model of the growth of the Kingdom of God, from an extremely tiny seed to the largest of all garden plants. They were also an example of the tiny amount of faith needed to accomplish much.

"You don't need to take a mustard seed with you as a symbol of your faith," minister and author Norman Vincent Peale wrote to White prior to the flight. "You have the faith itself, and the inner sturdiness that will carry you through this tremendous and rewarding experience."

"There goes your glove ..."

One artifact that did not return to Earth with White was his right comfort glove. [The Evolution of the Spacesuit in Photos]

"Oops, there goes your glove," McDivitt stated as he saw the optional over-glove float out the hatch while White was already out on his spacewalk.

White wore the matching glove pulled over the pressure gauntlet on his spacesuit, to help keep his hand warm.

"I had one thermal glove on the one hand, my left hand," he said after returning to Earth. "I always wanted my right hand to be free to operate that [zip] gun and the camera."

The right thermal glove seemed to take on a mission of its own.

"It floated out over my right shoulder and out," described White during a technical review. "It looked like it was on a definite trajectory going somewhere. I don't know where it was going."

"It floated very smartly out of the spacecraft and out into space," he said.

Go for EVA

Since Alexei Leonov and Ed White completed the first two spacewalks, more than 375 have followed, with some 260 of them by American astronauts.

The "go" for the first American spacewalk came only about a week before Gemini 4 was ready to launch. The mission plan originally called for White to only stand up on his seat and pop his head out the hatch, while McDivitt held onto him — or perhaps vice versa.

"Ed White will probably be the standee and I probably will hold onto him," McDivitt told the media at their pre-launch press conference.

"Yes, I'm the standee and he is the holdee," White added.

The move to go full EVA was made in direct response to Leonov's spacewalk on March 18, 1965. It still took NASA more than two months to decide White would float out of the capsule.

"We only had one final week of training when word came down from headquarters: 'We're go for EVA,'" flight director Gene Kranz recalled.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

Click through to collectSPACE to see photos of Ed White's mustard seeds, lost comfort glove and "patriotic patch."

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2015 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, an online publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018. He previously developed online content for the National Space Society and Apollo 11 moonwalker Buzz Aldrin, helped establish the space tourism company Space Adventures and currently serves on the History Committee of the American Astronautical Society, the advisory committee for The Mars Generation and leadership board of For All Moonkind. In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History.