Sampling Enceladus: Is Earth Ready for Pieces of Saturn Moon's Plumes?

Many astrobiologists are champing at the bit to bring back samples from Saturn's ocean-harboring moon Enceladus, but others say it may be best to exercise a little patience.

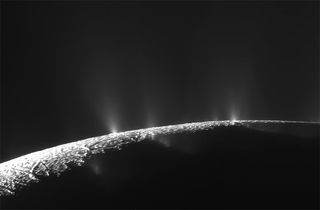

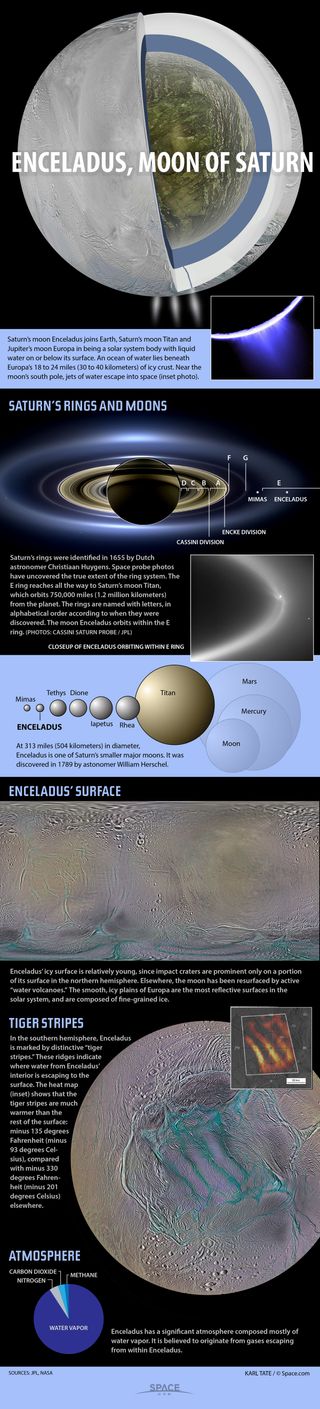

In 2005, NASA's Cassini spacecraft discovered that geysers blast from Enceladus' south polar region, sending material from the ice-covered moon's subsurface ocean far out into space. It's tempting to grab samples from Enceladus' plume and return them to labs on Earth for analysis as soon as possible, but a slower, more methodical plan may be the right way to assess the moon's life-hosting potential, one prominent space scientist says.

"Who is going to approve a sample-return mission if we're not sure the stuff in the plumes is worth bringing back to a terrestrial lab?" Brent Sherwood, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, said at the Astrobiology Science Conference in Chicago in June. [Photos: Enceladus, Saturn's Icy Moon Revealed]

"These are very hard decisions for decision makers to make when there are a lot of zeros after the dollar signs," added Sherwood, who manages the Innovation Foundry, which pulls together the conception, capture, planning and engineering of JPL space science missions.

Step by step

The 310-mile-wide (500 kilometers) Enceladus is one of the solar system's best bets to host alien life, researchers say. The satellite harbors large amounts of subsurface liquid water and also features an energy source: internal heat generated by the gravitational tug of Saturn.

Other worlds throughout the solar system — such as Jupiter moons Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, as well as the dwarf planet Ceres — are known or suspected to host underground oceans. NASA has already taken an intriguing first look at many of these worlds, thanks to the Voyager, Galileo, Cassini and Dawn missions, among others.

The next step, according to Sherwood, is to chemically characterize these worlds' oceans both directly and indirectly. If something interesting is found, then it needs to be confirmed. At that point, a consensus may be reached that sample return is a necessary step. (Analyzing samples in well-equipped labs on Earth is the best way to search for signs of alien life, many researchers say.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The best way to do all of this is to establish a step-by-step exploration program for the ocean worlds similar to the one NASA has developed for Mars, Sherwood argued.

"A lot of money has flowed into the prospect that Mars is habitable," he said.

Sampling the plumes

Enceladus is special among the ocean worlds because of the plumes; spacecraft can sample the moon's subsurface sea without even touching down. (NASA's Hubble Space Telescope spotted signs of plumes on Europa several years ago, but these phenomena have not yet been confirmed.)

But it's still preferable to conduct a detailed analysis of Enceladus' plumes in situ before mounting a sample-return mission, Sherwood said. Although Cassini has flown through the plumes and analyzed their components, the spacecraft wasn't designed with this task in mind.

Protecting Earth against potential alien contamination would be a significant issue, Sherwood added.

"You've got to demonstrate that you've got the means for planetary protection because you're bringing stuff back," he said.

Despite decades of in-depth study, no samples have been brought back to Earth from Mars, though NASA's Mars 2020 rover mission plans to cache material to return in the future.

Sherwood said achieving a sample-return mission to Enceladus requires step-by-step preparation. Given the estimated 14-year round trip such a mission would endure, not to mention the time spent developing missions, having a sample back on Earth by 2049 requires scientists to begin advocating today.

"A lot of scientists say, 'No, I don't want to wait that long because I'm not going to live that long," Sherwood said. "If you never get started, it takes infinitely long."

Every 10 years, the U.S. National Research Council's Decadal Survey looks into the future another decade to prioritize research areas, observations and potential missions. The next decadal survey will be published in 2021 and will affect decisions made in 2023. The survey is influenced by concepts submitted between 2018 and 2020, and has a September 2019 deadline.

This gives scientists a short period of time to influence the next era of discovery.

"We live in a pivotal time," Sherwood said. "One hundred years ago, no one could have imagined us doing the kind of exploration we're doing today."

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd