Cassini's Grand Finale Is Saving the Best Saturn Science for Last

As Cassini wraps up its 13-year mission in Saturn's system, scientists are preparing for the spacecraft's final burst of observations in the never-before-explored region between the planet and its inner rings.

Cassini crossed Saturn's ring plane for the first time today (April 26). Next, after a series of 22 orbits and close flybys of the rings, the robotic probe will take a death dive into the planet's atmosphere on Sept. 15.

"We're going to have to say goodbye to this amazing mission," said Athena Coustenis, a Cassini co-investigator at the Paris Observatory in France. [Cassini's 'Grand Finale' Saturn Orbits Explained (Video)]

"I have another five months to get very emotional about it," Coustenis told reporters yesterday (April 25) during a news conference at the annual meeting of the European Geosciences Union (EGU) in Vienna. "In the meantime, we're going to have the opportunity to top off this wonderful mission with a lot of new measurements for the rings and for Saturn's interior."

The best views for last

The final flybys will be a "dangerous moment for the mission," said Luciano Iess, a Cassini team member from La Sapienza University in Italy. The spacecraft will be moving at a speed of about 30 kilometers per second, or 67,000 mph (42,000 km/h), passing rocks and tiny particles as it grazes the ring planes. If those orbits are successful, scientists will have a chance to examine the material in Saturn's mostly water-ice rings in greater detail than ever before, which could help them determine the mass and age of the rings.

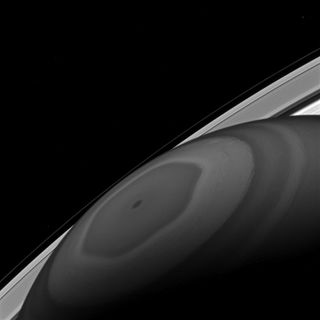

Cassini recently obtained some of the closest-ever images of the outer edges of Saturn's main rings. During the spacecraft's upcoming ring-skimming orbits, scientists anticipate that they'll get an even better look at strange features in the rings' structure, such as the clumps of ring particles known as "straw" and structures known as "propellers" that are thought to be produced by the gravitational pull of Saturn's moonlets and sometimes stretch several thousand miles long.

Cassini's final observations also promise to provide even better images of smaller moons — like ravioli-shaped Pan, ring-sculpting Daphnis and the flying-saucer-like Atlas — that orbit in the gaps between Saturn's rings, Coustenis said. She added that scientists will get views of Saturn's northern hemisphere in greater detail, which could offer new information on the planet's clouds and hazes at different altitudes, and observations of auroras could provide new insight into Saturn's magnetosphere.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Cassini's next five months could reveal new clues about the somewhat mysterious interior structure of Saturn, too.

"Magnetic field and gravity measurements are the only tools that are able to go deep, below the cloud layer," Iess told reporters at the news conference. "They tell us about the deep interior structure of the planet."

Measurements of Saturn's gravitational field could help scientists determine how much hydrogen and helium are in the outer layers of Saturn, as well as the quantities of heavy elements concentrated in the core, Iess added.

Past studies indicated that Saturn's magnetic field is weaker than expected and that, surprisingly, it's aligned with the planet's rotation. Scientists might be able to explain those unexpected findings if they can identify the sources of Saturn's magnetic field with measurements from Cassini's magnetometer.

Gravitational and magnetic measurements together could also determine the depth of Saturn's strong winds that whip at up to 500 mph (800 km/h) and produce the huge bands in the planet's atmosphere, Iess said.

Cassini's big breaks

Scientists at EGU reflected on the past 13 years of discoveries by Cassini, which is a collaboration among NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Italian Space Agency.

"Nothing that came out of this mission was really expected or imagined or modeled before," Coustenis said. "We had many surprises that actually led us to review our models, led us to rethink our whole concept of the outer solar system."

For example, because of Cassini data, scientists have had to revise their understanding of the habitable zone in the solar system, Coustenis said. While it was once believed that habitable bodies needed liquid surface water as on Earth, solar system objects such as the icy moons around Jupiter and Saturn — many of which appear to have subsurface oceans —are now a new source of excitement. Recent findings based on Cassini's observations of Saturn's moons Titan and Enceladus "have proved to us that the habitable zone is actually not restricted to surface habitats; we could have liquid water under the surface," Coustenis said.

J. Hunter Waite, a scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, recently led a team of researchers in analyzing observations made by Cassini during an October 2015 dive through a geyser plume shooting out of Saturn's icy moon Enceladus. Their results, which were published earlier this month, suggested that life-sustaining chemical reactions could be occurring in Enceladus' subsurface ocean.

"We got water; we got organics; we got an energy source," Waite told reporters at the news conference. "This place is by all accounts a habitable ocean in the interior of Enceladus, and that's quite exciting."

But Waite told Space.com that a new mission with new instrumentation will be needed to really search for life.

There are two missions being prepared that could further explore the question of habitability in the subsurface oceans on icy bodies in the outer solar system: ESA's JUICE (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer) mission, planned to launch in 2022, and NASA's Europa Clipper, planned to launch sometime in the 2020s, which will investigate Jupiter's icy moons Ganymede and Europa, respectively.

Regardless of what they learn from future missions, scientists will be trying to make sense of Cassini data long after the spacecraft's final plunge.

"I worked on the Voyager mission 10 years after the mission itself," Coustenis said. "You can imagine how long we're going to be working on the Cassini mission in the future."

Follow Megan Gannon @meganigannon, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.