What Earth's Oldest Fossils Mean for Finding Life on Mars

If recent findings on Earth are any guide, the oldest rocks on Mars may have signs of ancient life locked up inside.

In a new study, a team of geologists led by Allen Nutman, of the University of Wollongong in Australia, discovered 3.7-billion-year-old rocks that may contain the oldest fossils of living organisms yet found on Earth, beating the previous record by 220 million years. The discovery suggests that life on Earth appeared relatively quickly, less than 1 billion years after the planet formed, according to the new research, published online today (Aug. 31) in the journal Nature.

If that's the case, then it's possible that Martian rocks of the same age could also have evidence of microbial life in them, said Abigail Allwood, a research scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Allwood was not involved with the new study but authored an opinion piece about the discovery, which was also published today in Nature. [7 Theories on the Origin of Life]

"It's clear Mars had a similar early history to Earth," she told Live Science. Many scientists think Mars may have been warmer and wetter in the past, conditions that may have supported microbial life.

Allwood is the principal investigator for the PIXL instrument on the planned Mars 2020 rover, which will use X-ray fluorescence to determine the relative abundance of different elements in Martian rocks. A roving probe, she said, will be able to take samples of local rocks and test them, and see if there are any signs of ancient life on Mars.

In their new study, Nutman and his colleagues found a kind of rock structure known as a stromatolite — layers of minerals left by single-celled creatures, among some of the first life-forms that evolved on Earth.

The rocks were found in Isua, Greenland. Even though they are among the oldest rocks on Earth, they aren't the sedimentary rocks that fossils are typically found in, noted Nutman. Instead, they are metamorphic rocks, which means they have been repeatedly heated and cooled over the last few billion years. But the heating wasn't so great that the stromatolites were destroyed. "They were heated to a maximum of about 500 degrees [Celsius, or 930 degrees Fahrenheit]," Nutman said. "The rocks also didn't have too many outside fluids going through them." In fact, the chemistry of the rocks showed evidence of seawater.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Allwood said on Mars, sedimentary rocks are actually better preserved than on Earth, because Mars lacks plate tectonics. (Plate tectonics are the forces that alter the surface of Earth as plates constantly shift over the planet's mantle.)

"No plate tectonics means no metamorphosing," she added. This means anything like a stromatolite on Mars would be more likely to have survived to now.

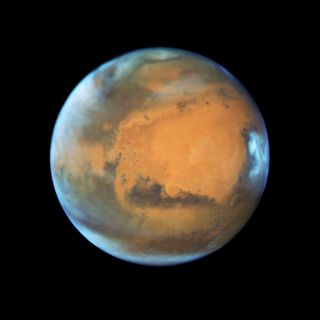

Planetary scientists have found places on Mars that resemble ancient flood plains and basins, called delta deposits. These regions not only suggest that water once flowed on the Red Planet, but that they could be good places to look for any existing remains of ancient life-forms.

"The Isua paper makes a case for looking at that ancient environment," Allwood said. "I think if you strategically sampled almost any of those, you'd probably find evidence of life."

Original article on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.

Most Popular