ALMA 'Weighs' Monster Black Hole to Highest Precision

Though we know black holes are kinda big, how do astronomers measure their mass? It's not as if we can go out there and simply "weigh" them. Fortunately, astronomers have many tricky ways to work out the mass of objects in the universe and black holes are no exception.

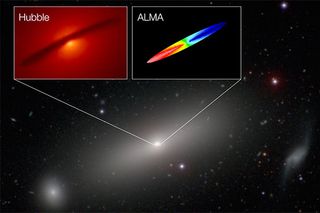

Using the biggest and most powerful observatory on the planet, astronomers have been able to zoom in on the central region of an elliptical galaxy called NGC 1332, around 75 million light-years away, to get a high-precision view of the swirling gases around the central supermassive black hole. Although most known galaxies are now known to contain these black hole behemoths in their cores, this particular beast is quite the specimen: it's 660 million times the mass of our sun.

PHOTOS: Monster Desert Telescope Construction Complete

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile was used to achieve this high-precision feat, but it didn't look at the black hole directly, it measured the furious storm of galactic gases stuck inside the deep gravitational well of the black hole.

"To calculate the mass of a black hole in a galaxy's center, we need to measure the speed of something orbiting around it," said Aaron Barth, of the University of California, Irvine, and lead author of a study published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters. "For a precise measurement, we need to zoom in to the very center of a galaxy where the black hole's gravitational pull is the dominant force.

"ALMA is a fantastic new tool for carrying out these observations."

As we all know, black holes are, well, black. Their mass has such an immense gravitational pull that nothing, not event light, can escape. As we can't see them (as there's nothing to see as there's no escaping light), astronomers have to look for black holes' presence through other, indirect, means. One way is to measure the emissions of the hot gas trapped in a black hole's accretion disk, for example. Another is to see how a black hole's mass will warp spacetime, bending (or lensing) light around it.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

NEWS: 'Bizarre' Group of Distant Black Holes are Mysteriously Aligned

But in this case, cold molecular gas could be seen in the vicinity of NGC 1332's black hole. Knowing the distance of the gas cloud from the black hole and using ALMA to clock its speed, a highly precise measurement of the black hole’s mass could be made. And this one is certainly in the heavyweight division of supermassive black holes.

In the case of this galaxy, the gas has flattened out into a vast disk of spinning matter about the black hole with a radius of 800 light-years. Keep in mind that the distance from our solar system to the nearest star system, Alpha Centauri, is a little over 4 light-years, the radius of this structure is a whopping 200 times wider. At visible wavelengths, this disk cannot be resolved and just appears as a silhouette against a background of densely-packed stars (as can be seen in the image, top). ALMA, however, observes the cosmos in radio wavelengths and the cold gas disk generates radio emissions, allowing the astronomers to resolve small structures, only 16 light-years wide, inside the disk.

This stunning precision allowed measurements of the spinning gas within the black hole's "sphere of influence" — a region within 80 light-years of the black hole — that is dominated by the black hole's gravity, and its speed could be found. The gases in this region are whipping around the black hole as an awesome speed of over 300 miles per second.

ANALYSIS: How Do You 'Weigh' a Spiral Galaxy's Monster Black Hole?

Previous measurements of black hole masses have relied on observing the visible light from the ionized gas in hot accretion disks. Though observatories like the Hubble Space Telescope have been able to calculate the mass of black holes by doing this, hot accretion disks are, by their nature, highly turbulent. This adds a large degree of uncertainty in visible light measurements.

But the emissions from cold molecular gas (in this case, the emissions generated by carbon monoxide, or CO) in extended disks originate from far more quiescent environments, providing astronomers with an incredibly powerful tool to remotely measure how massive these galactic monsters really are.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Ian O'Neill is a media relations specialist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California. Prior to joining JPL, he served as editor for the Astronomical Society of the Pacific‘s Mercury magazine and Mercury Online and contributed articles to a number of other publications, including Space.com, Space.com, Live Science, HISTORY.com, Scientific American. Ian holds a Ph.D in solar physics and a master's degree in planetary and space physics.