Why Do We Love Space Movies?

In space, no one can hear you spill your popcorn. But we see it floating everywhere, expanding, exploding in slow motion. And it's that dreamlike, otherworldly, heavenly, uncanny feeling that makes us gravitate toward space-themed screens, again and again.

As Douglas Adams wrote in "The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy," "Space is big. Really big." It's a place of limitless possibility. Its spatial-temporal vastness suspends disbelief. Space allows for, among other wonders, "Star Trek" creator Gene Roddenberry's "Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations" — a ready surplus of places for movie plots.

The substance of all other cinema — every action picture, big-screen drama, comedy, musical, documentary, animated feature, newsreel; every big-budget blockbuster and self-produced short — takes place within the atmosphere of one tiny, insignificant planet. It's called "Earth," in one of the languages spoken by one of its semi-sentient species. This is, of course, equally true of literature: Viewed from the lofty perch of orbit, all other fiction is but a subset of sci-fi.

Space fiction plotlines bounce back and forth between prose and movie scripts, sometimes stealing outright from one another across decades in unexpected ways. Read Edgar Rice Burroughs' "A Princess of Mars" (1912), and then watch James Cameron's "Avatar" (2009). (But don't see Disney's "John Carter"— I beg you.)

Space is, after all, called "space" for a reason. There's infinite room to fly, hide, love, fight, laugh and fear. Getting beyond the assumptions of Earth allows the filmmaker a much broader canvas on which to paint "What if?"

We go to the movies to escape — and you can't get any farther away than deep space. Our personal disappointments, dramas and emotional dissonances suddenly seem far more distant and diffused. Want perspective? Catch a space flick.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In 70 years of space exploration, a handful of milestone missions have stood out: Vostok 1 in low Earth orbit (1961), Apollo at the moon (1969), Mariner 9 at Mars (1971), Viking at Mars (1976), The Voyagers' grand tours (begun in 1977), Hubble Space Telescope deployment (1990), Clementine over the moon's south pole (1994) and a few more. These missions made model-shattering discoveries that forever altered the trajectory of scientific and commercial endeavors.

So, too, in the space cinema, a few special films set the art off in entirely different directions, on new types of quests, exposing us to new worlds.

The biggest screen

Georges-Jean Méliès' 1902 film "A Trip to the Moon" — one of this planet's first science fiction films — drew upon the pulp fiction literature of its day: Jules Verne's "Around the Moon" and "From the Earth to the Moon," and a few other works by lesser-known authors.

Méliès — who made more than 500 films, many of which were sci-fi, fantasy and horror — invented dozens of cinematic special effects, motion photography and staging techniques. And he brought the first aliens to the screen: exoskeleton-clad, bug-headed monsters of the moon. (Neill Blomkamp's "District 9" would echo these creatures 107 years later.) Sadly, the movie industry's winning business model lay undiscovered, years in Méliès' future, and he died a destitute candy salesman, financially undone by the rapacious business practices of Thomas Edison. Méliès' life story could make a good movie (the 2011 film "Hugo" was a partial telling of Méliès' career).

By the 1950s, space in film had mostly devolved to the origin point of cheap, campy creatures inhabiting B-movie horror flicks. These movies seemed designed solely to bring couples together in the one public place that repressive society allowed public mating rituals. Viewers — perhaps your forebearers — clutched each other when the guy in the rubber suit stumbled, snarling on-screen.

And that was all there was to the genre, until "Forbidden Planet" (1956). Drawing together the plot of Shakespeare's "The Tempest" with the hard tech feel of interstellar travel, this risky big-budget film showed what imagination can do to an audience — but only if the filmmakers respect their viewers' intelligence.

"Forbidden Planet" successfully landed in formerly forbidden filmmaking territory. Never before had a film been set entirely on an alien world, nor had its human characters arrived in a superluminal (faster-than-light) ship. The movie's obligatory monster turns out to be quintessentially human. The warm beauty of ingénue Anne Francis' Altaira character is outshone by the surprising humanity of Robbie the Robot. An all-synthesized music score, alien to the ears of the time, transported moviegoers out of their comfort zone. And Leslie Nielsen created the prototype for starship captains that William Shatner would, a decade later, adopt into "shtick."

In 1968 — the year humans first orbited the moon — Stanley Kubrick brought one of the most beloved space movies of all time to the screen: "2001: A Space Odyssey." Exquisitely detailed spacecraft, designed by Fred Ordway and Harry Lange (both ex-NASA), and true-to-life pop-culture references suspend your disbelief. A storyline stretching longer than the history of the human species blows the hatches off your psyche. The film's pedigreed plot, from author Arthur C. Clarke, hints that humanity's evolution was directed by something from Out There. And Kubrick warns the generations of computer coders who would come after what happens when you give a highly capable artificial intelligence conflicting instructions. (See Space.com's infographic: "2001: A Space Odyssey")

Andrei Tarkovsky's "Solaris" (1972) — and its (1992) Steven Soderbergh remake, both based on Stanislaw Lem's novel — proved that the scariest place in the universe might lie inside the human mind.

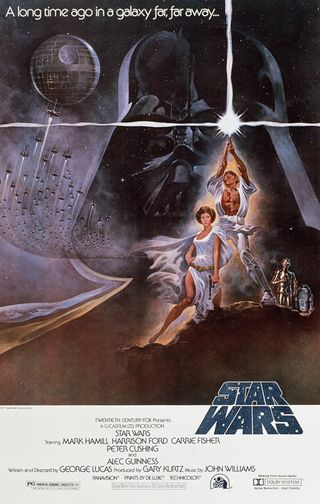

In 1977, "Star Wars" introduced us to a galaxy far, far away. 'Nuff said.

With 1977's "Close Encounters of the Third Kind," Stephen Spielberg lofted the status of on-screen aliens from dirt bags to angels. Finally, the non-faith-based yet near-religious mysticism of advanced intelligent extraterrestrial space travelers, long a trope of science fiction literature, was brought faithfully to the cinema.

Ridley Scott's "Alien" (1979) went the opposite way, showing us the most terrifying alien yet, but finally removing the curse of "camp" from the horror genre in space. Scott and actress Sigourney Weaver gave us the first strong female leader of the sci-fi screen genre with the character Lt. 1st-Class Ellen Ripley. [Watch for Weaver in a new "Alien" franchise film, now in production with director Neill Blomkamp.]

In 1983, Philip Kaufman directed an adaption of Tom Wolfe's book "The Right Stuff." This largely true-to-life docudrama emotionally colors in the black-and-white history of the early United States' "manned" space program. This film deftly shows that the reasons America went to space when it did were as much cultural as technological. And we learn why all astronauts and airline pilots sound the same on microphones.

"The Right Stuff" set the stage for "Apollo 13" (1995), which — as director Ron Howard once pointed out to this reporter — succeeds even though the film contains no sex, no human violence and no villains.

1999's "Galaxy Quest" proved we fan-folk are not afraid to laugh at ourselves, and at our love of space opera.

"Moon" (2009), from director Duncan Jones, rebooted the genre by bring us back to story instead of visual effects. Isolation amid the universe is something each of us experiences in whatever space we inhabit. And paranoia is sometimes justified; if it weren't a survival skill, we would have probably lost it long ago.

By 2013, with most moviegoers unable to personally recall a time before real-life astronauts, director Alfonso Cuarón brought forth "Gravity." Sandra Bullock grabs your full attention in every frame, as her castaway character Ryan Stone must confront herself to survive. Space, in this film, is the agent of death and transfiguration. In a 2013 interview with Space.com, Cuarón described "Gravity's" spacecraft-as-cocoon metaphor: Within a ship or a spacesuit, you are temporarily safe, but you must venture out from the nest in order to survive. Each one of us goes through this transition — with varying degrees of success — as we grow up — or try to, or refuse to.

2015's "The Martian," directed by Scott, quickly paid for itself at the box office. It's another "actor's movie" — a true tour de force for lead Matt Damon. Mars is cast as Scott's "magnificent monster," one that the real NASA and its partners are trying to tame. Space in movies thereafter would just be another setting, like an ocean or a desert. (Read Space.com's exclusive interview with Sir Ridley Scott.)

An actor's universe

Up off this mud ball, however, actors and directors can stretch out. Things are often simpler in space — stark choices and sharply definable feelings. Performers and producers can explore different physics, and react in different ways.

Astronaut characters, even badass villains, start from a stature of significance. Audiences look up to high fliers. We come to the theater, or tablet screen, preprogrammed with a need to respect them. We assume they've been tested under pressure. Part of the filmmaker's shorthand is that a spacesuit, however shabby or distressed, is a robe of royalty. Even the weak and weedy ones (looking at you, Luke Skywalker) get a free pass from us.

We watch and we inhabit every astronaut character. We wonder what we would do in their moon boots. Death is always seconds away for any cinematic spacefarer. Through them, we live the naked drama of "me against the universe." As actor Tom Hanks has said, "Whenever I'm in a spacesuit, I'm Dave Bowman," referring to the astronaut character from "2001: A Space Odyssey," played by Keir Dullea.

Digital dreams and coming attractions

Since Méliès began the art, depicting space on film has called for ingenuity. Kubrick's "2001" pushed the envelope of analog photographic effects in unexpected directions. "Star Wars" (1977) begot the now legendary effects facilities Industrial Light and Magic (ILM) and Skywalker Sound, and ignited an explosion of digital filmmaking.

Principal photography for James Cameron's "Avatar" (2009) had to wait a more than a decade after it was first scripted for the required filmmaking technology to mature. Cameron teamed his proprietary 3D Fusion Camera System with a powerful digital graphics engine to create "simulcam." This system allowed the writer/director to see, in real time, his actors' performances seamlessly composited in completely computer-generated scenes — and, importantly, to show the actors immediate "in-world" playback while giving notes. George Lucas and Steven Spielberg came to Cameron's set to observe how such augmented reality (AR) could augment filmmaking. (Watch for three "Avatar" sequels — now in production — due to premiere in 2017, 2018 and 2019.)

Cuarón's "Gravity" (2013) also thrust forward the artful edge of cinema technology. The "Gravity" crew invented a new way to put characters in space by filming them inside a box made essentially of video monitors. This rig projected synchronized lighting detail motivated by the scene. The resulting dramatic performances already contained the lighting, which the yet-to-be-created digital images would "throw." By the time an audience saw them, the only analog element remaining in many shots was Bullock — and sometimes, only her face or hand.

With this new century's marriage of the camera and the computer, directors have no creative limits, only budgetary ones. If you can dream it, you can screen it.

Digital filmmakers no longer use the word "simulate." Now they "realize."

Immersive virtual reality (VR) is in its infancy. Oculus, Samsung and other would-be VR experience providers are contending with hardware. Screen refresh rates are not yet fast enough to convince us we're in VR space without making us puke in the real analog world. But we can see, off in the not-so-far distance, a movie landscape shifted to immersion (you and me in the scene) and, eventually, to interaction (you and me affecting the storyline). Based on cinema's history, it's likely that market demand for escapist entertainment will drive this technology to maturity.

The hardest challenge for the filmmaker, then, will be to "realize" our popcorn floating in space, until we eat it back here in the real world.

[Editor's Note: Be sure to check out Space.com's official list of Best Space Movies in the Universe, and for something a little different, take a look at our list of Strange and Lesser-Known Space Movie Favorites.]

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Dave Brody has been a writer and Executive Producer at SPACE.com since January 2000. He created and hosted space science video for Starry Night astronomy software, Orion Telescopes and SPACE.com TV. A career space documentarian and journalist, Brody was the Supervising Producer of the long running Inside Space news magazine television program on SYFY. Follow Dave on Twitter @DavidSkyBrody.