Spaceflight Changes the Shape of Astronauts' Brains

It appears that spaceflight really goes to astronauts' heads.

Doctors and scientists have long known that exposure to a weightless environment causes muscles to atrophy, bones to weaken and vision to deteriorate, among other effects. Now, a new study has determined that spaceflight also causes some parts of the brain to expand and others to contract. [The Human Body in Space: 6 Wild Facts]

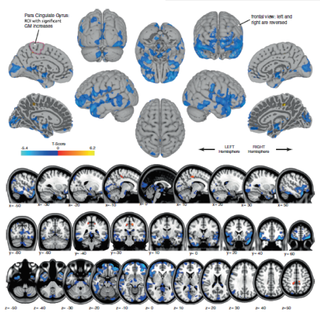

"We found large regions of gray-matter volume decreases, which could be related to redistribution of cerebrospinal fluid in space," study principal investigator Rachael Seidler, a professor of kinesiology and psychology at the University of Michigan, said in a statement.

"Gravity is not available to pull fluids down in the body, resulting in so-called puffy face in space," Seidler added. "This may result in a shift of brain position or compression."

Seidler and her team studied magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of 26 astronauts — 12 who flew on two-week-long space shuttle missions, and 14 others who lived aboard the International Space Station (ISS) for five to six months.

The brain regions that expanded are associated with the control of leg movement and the processing of sensory information from the lower body, team members said. Therefore, the MRIs are likely capturing the brain learning a new skill — how to move in microgravity— and doing so around the clock, Seidler said.

"It's interesting, because even if you love something, you won't practice more than an hour a day," she said. "In space, it's an extreme example of neuroplasticity in the brain, because you're in a microgravity environment 24 hours a day."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It's unclear how long these changes last after astronauts come back to Earth, or how the shifts may affect cognitive ability, the researchers said. Seidler and her team are currently conducting another long-term study to look into these questions.

The new study was published in December 2016 in the journal Nature Microgravity. The lead author is Vincent Koppelmans, of the University of Michigan's School of Kinesiology.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.