The End is Near for NASA's Historic Dawn Mission to the Asteroid Belt

Appreciate those gorgeous photos of the dwarf planet Ceres that NASA's Dawn spacecraft keeps beaming home, because that tap will soon run dry.

Dawn — the only probe ever to orbit two objects beyond the Earth-moon system — will likely run out of fuel in the next month or so, between mid-September and mid-October, mission team members said today (Sept. 7).

When that happens, the venerable probe will lose the ability to orient itself as needed to study Ceres or transmit data back to its controllers on Earth. Dawn will become a cosmic ghost, orbiting the dwarf planet in silence for decades to come. [Photos: Dwarf Planet Ceres, the Solar System's Largest Asteroid]

"Although it will be sad to see Dawn's departure from our mission family, we are intensely proud of its many accomplishments," Lori Glaze, acting director of NASA's Planetary Science Division, said in a statement yesterday (Sept. 6). "Dawn's science and engineering achievements will echo throughout history."

A long road

The $467 million Dawn mission launched in September 2007, tasked with performing up-close reconnaissance of the two biggest bodies in the asteroid belt: the 590-mile-wide (950 kilometers) Ceres and the 330-mile-wide (530 km) protoplanet Vesta.

Scientists regard Ceres and Vestaas relics from the solar system's early days — leftovers that didn't get incorporated into bigger worlds such as Mars and Jupiter. This explains the name Dawn, which is not an acronym.

Dawn reached Vesta in July 2011 and studied the object from orbit until September 2012, when the probe departed for Ceres. Dawn arrived at this latter destination in March 2015, becoming the first — and, so far, only — spacecraft ever to orbit a dwarf planet. (NASA's New Horizons spacecraft famously zoomed past the dwarf planet Pluto in July 2015, but that was a flyby; there was no orbiting involved.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Dawn was able to accomplish these exploration feats thanks to its superefficient propulsion system, which generates thrust by expelling ions of xenon from a nozzle. Dawn's engine isn't very powerful — it would take the probe about four days to go from 0 to 60 mph (100 km/h) — but the craft can reach tremendous speeds because it can fire those engines continuously for long stretches.

"This is what I like to think of as 'acceleration with patience,'" Dawn mission director and chief engineer Marc Rayman, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, said during a news conference today. "It opens up destinations in the solar system that NASA would otherwise be completely unable to reach."

Dawn isn't about to run out of xenon, by the way. The fuel it's low on is hydrazine, the conventional propellant that powers Dawn's smaller, orientation-changing thrusters.

Scientific bounty

Dawn's work at Vesta and Ceres has revealed many details about these two bodies as well as the solar system's early history.

For example, Dawn's observations showed that Vesta's northern half has a surprising profusion of craters, suggesting that the asteroid belt harbored more big objects long ago than researchers had thought, mission team members said. And Dawn's measurements confirmed that Vesta is the source of howardite, eucrite and diogenite meteorites, a family that's common here on Earth.

And then there's Ceres. The dwarf planet is much icier than the dry, rocky Vesta, strongly suggesting that the two bodies formed in very different places — Vesta closer in, in the realm of the rocky planets like Earth and Mars, and Ceres farther out, in the cold depths where ices could survive. (Ceres has migrated inward to its present location.)

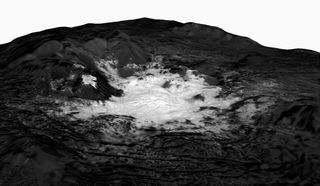

And Dawn has discovered a variety of interesting features on Ceres, including the 3-mile-high (4.8 km) "lonely mountain" Ahuna Mons and strange, bright spots speckling the floors of many craters.

Dawn's observations revealed that these bright deposits consist of salts such as sodium carbonate. Scientists think these salts were left behind after briny water bubbled up to the surface from underground reservoirs and boiled off into space. [Photos: The Changing Bright Spots of Dwarf Planet Ceres]

The deposits are young, so this activity has occurred very recently. Indeed, Ceres almost certainly retains some briny liquid underground today, said Dawn principal investigator Carol Raymond, also of JPL.

"We know there is an active geological cycle that's bringing material from deep up to the surface, and that gives us the opportunity to sample some of Ceres' interior material by sending a mission to the surface," Raymond said during today's news conference.

NASA is already thinking about what a surface mission might look like, agency Chief Scientist Jim Green said during today's event. Nothing is on the books, but NASA has held meetings to start mapping out potential architectures, Green said.

"The body is so intriguing in so many ways, we've just absolutely got to go back," he said.

Left aloft

The end-of-life plan for Dawn is quite different from the one NASA devised for its Saturn-orbiting Cassini spacecraft.

The low-on-fuel Cassini was steered to a fiery death in the ringed planet's atmosphere last September, to ensure the probe never contaminated the Saturn moons Titan or Enceladus — both of which may be capable of supporting life as we know it — with microbes from Earth.

But Ceres has no appreciable atmosphere, so incinerating Dawn is not an option. Instead, the mission team will just leave the probe in its current orbit around Ceres — a highly elliptical path that brings it as close as 22 miles (35 km) to the surface, and as far away as 2,500 miles (4,000 km).

NASA planetary-protection guidelines dictate that Dawn not crash into Ceres' icy surface for at least 20 years, Rayman explained in a recent blog post. This window gives NASA time to mount another mission to an uncontaminated Ceres, if the agency decides to do so.

Dawn's current orbit is more than stable enough to meet that requirement, Rayman noted today.

"Our analyses give us very high confidence — greater than 99 percent — that it [Dawn] will stay in orbit for even half a century, and most likely longer than that," he said during the news conference.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.