Catalog of Earth Microbes Could Help Find Alien Life

If an alien planet in a distant solar system were home to microscopic life-forms, how might scientists see them and even decipher their identity? A new catalog of Earth-based life-forms may provide a first step.

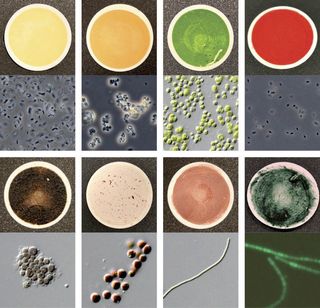

Scientists at Cornell University rounded up 137 microorganisms and cataloged how each life-form uniquely reflects sunlight. This database of individual reflection fingerprints, which is available to anyone, might help astronomers identify similar microscopic life-forms on distant alien planets.

"This database gives us the first glimpse at what diverse worlds out there could look like," Lisa Kaltenegger, professor of astronomy and director of Cornell University's new Institute for Pale Blue Dots, said in a statement. [10 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

Seeing life on other planets

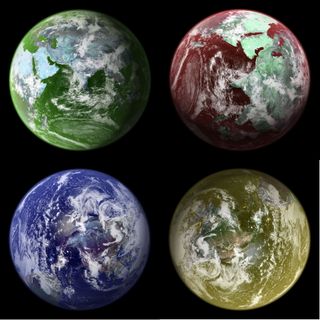

If alien beings living on a planet many light-years away from Earth were to point their telescopes at our planet, they might be able to catch a glimpse of sunlight bouncing off its surface. This reflected light is also known as the planet's spectrum, or basically, its color.

Earth's spectrum would be a shade of green, according Kaltenegger, because a significant portion of our planet's surface is covered in green plant life. Based on this observation, those alien astronomers could potentially deduce that life exists on our planet.

Scientists on Earth would like to look at the spectra of alien planets in the hope of identifying signs of life. Astronomers are just starting to see the spectra of planets outside our solar system, and have plans to build even better tools for this task.

The goal of the new catalog, say the authors, is to provide planet hunters and astronomers with a baseline comparison: this is what the color spectra of Earth-based microscopic organisms would look like from afar. Astronomers can, hypothetically, compare these spectra of known organisms with those seen on other planets. Studying the spectra of life on Earth might give them an idea of what the spectra of life will look like on other planets.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A first step

To create the new catalogue of microbial spectra, the researchers used a spherical apparatus that shines light on the microbial samples, and captures the distinct way each organism reflected sunlight, regardless of the angle at which the sample was viewed.

With spectral-analysis tools, scientists are able to see a detailed breakdown of an object's spectrum, so two objects that appear, to the human eye, to be the same shade of green, may actually have subtle color differences. Scientists can also gather wavelengths of light that can't be seen with the human eye.

The researchers who built the new catalog found that each organism had a slightly different color spectra — similar to how each person has individual fingerprints.

In theory, that means astronomers could identify a specific type of microorganism living a planet's surface, based on its spectrum. Kaltenegger notes that this would require the microorganism was dominant over the planet's surface. A more diverse culture of organisms would produce a cluttered spectrum of light bouncing off the planet. Kaltenegger says no other databases of this type exist, and already, planetary scientists are getting excited.

Mercedes López-Morales, an observational astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, contacted Kaltenegger shortly after the catalog was released, to express how exciting it was for her and her colleagues.

"This is exactly what we need," López-Morales said. "The main unknown is what to look for. We have no idea what the spectra on other Earth-like planets are going to look like."

Morales-López said it is possible the catalog will never be put to use: perhaps astronomers won't find planets with these type of spectra. Or maybe they won't be able to image the reflected light from a planet simply because of clouds, or the overwhelming reflection from water on the planet's surface.

"But at least now we have a guideline of what to look for," she said.

Now, the study's lead author, Siddharth Hegde, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (formerly of Cornell), is going further with this line of inquiry. He's working on understanding what physical factors are likely to make the most difference in the observed spectra, according to Kaltenegger.

For example, Hegde and the other researchers showed that microbiomes living in very different environments (like deserts vs. marshes) can still have very similar color spectra. With this kind of information, scientists can begin to further interpret the spectra they hope to gather from exoplanets.

The planet hunt

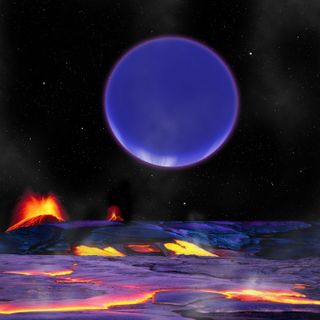

The hunt for life on other planets is heating up, but at the moment there are only a handful of candidates for exoplanets that could host life as we know it. But a recent study by scientists at the Australian National University and the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen predicts that billions of the stars in the Milky Way will have one to three planets in the habitable zone (the region around a star where temperatures are right for liquid water).

Meanwhile, the space-based Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope mission, or WFIRST, which is set to launch in 2024, will be equipped with tools for imaging planet spectra. So will the European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT), a ground-based, 131-foot-wide (40 meter) telescope also set to come online in 2024.

The new catalog of life-forms is an early step in helping scientists interpret the data that comes back from telescopes like WFIRST and E-ELT. While finding life elsewhere in the universe may seem like a far-off dream, López-Morales is confident scientists are well on their way to reaching it.

"I'm guessing that in 15 years we probably will have the first spectrum of a planet like Earth in our hands," she said. "Whether we will be able to fully interpret that spectrum is another story. But unless something goes really wrong — 15 years."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter

Most Popular