A Blue-Velvet Universe: Very Large Telescope Captures Invisible Glow of Deep Space

The whole sky appears to glow in a new photo from the European Southern Observatory (ESO).

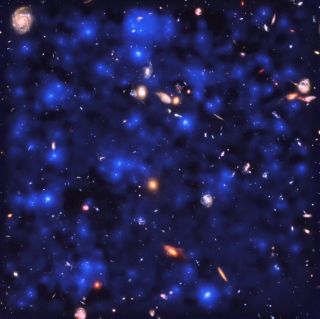

An international team of astronomers used the special eyes of the incredibly sensitive MUSE instrument on ESO's aptly named Very Large Telescope. The team peered into the Hubble Ultra Deep Field region and found "an unexpected abundance" of emissions from the early universe.

From their observations, the researchers extrapolated that almost all of the sky is invisibly glowing, like this scene, as dim yet abundant clouds of hydrogen imperceptibly produce Lyman-alpha emissions. [Found Them! 72 Unseen Galaxies Found Hiding in Plain Sight]

"This is a great discovery!" said team member Themiya Nanayakkara in an Oct. 1 photo caption by ESO. "Next time you look at the moonless night sky and see the stars, imagine the unseen glow of hydrogen: the first building block of the universe, illuminating the whole night sky."

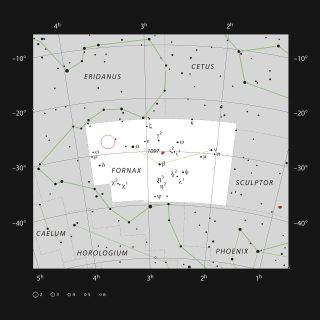

This composite image shows the faint Lyman-alpha radiation in blue superimposed on the popular image of the Hubble Ultra Deep Field taken by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2003 and 2004. Hubble collected light for over 270 hours to produce the original image of thousands of distant galaxies, ESO officials said in the caption, in what was then the deepest view of the universe. This region of the sky is found in Fornax, the constellation whose names translates to "the Furnace."

"Realising that the whole sky glows in optical when observing the Lyman-alpha emission from distant clouds of hydrogen was a literally eye-opening surprise," team member Kasper Borello Schmidt said in the caption.

MUSE sits atop the Very Large Telescope at ESO's Paranal Observatory in Chile. As an integral field spectrograph, it can view the sky in different light wavelengths. According to team member Philipp Richter, observations taken with MUSE can help astronomers capture images of the gas cocoons that envelope the galaxies in the early universe.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter@salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook. Original article onSpace.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.