Time to Celebrate: Ancient Sundial Made to Honor Roman Politician

About 2,000 years ago, a Roman politician celebrated his victory by commissioning a sundial and putting it on display for all to see, according to archaeologists who just discovered the ancient timekeeping device in Italy.

It's incredible the sundial and the inscriptions on it survived intact for two millennia, especially because the town was scavenged for building materials during the medieval period, the researchers said.

However, even though the sundial was found facing down in an amphitheater, archaeologists suspect the Romans had originally placed it in a more prominent spot in town — likely on top of a pillar in the nearby forum, they said. [Photos: Ancient Sundial-Moondial Discovered]

"Less than a hundred examples of this specific type of sundial have survived and of those, only a handful bear any kind of inscription at all, so this really is a special find," Alessandro Launaro, a lecturer at the Faculty of Classics at Cambridge University and a fellow at Gonville and Caius College, in the United Kingdom, said in a statement.

Students from the University of Cambridge found the sundial during the excavation of an amphitheater in the Roman town of Interamna Lirenas, located about 90 miles (144 kilometers) southeast of Rome.

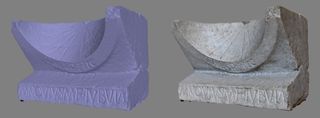

The limestone sundial measures about 21 inches by 13 inches by 10 inches (54 by 35 by 25 centimeters), and has a bowl-like face engraved with 11 hour lines, which mark the 12 hours of daylight. Three curved lines intersect perpendicularly with these hour lines, marking when the winter solstice, equinox and summer solstice should happen, the researchers said.

The sundial's iron needle that casts shadows — known as a gnomon— is missing, but its lead base is still there, the researchers noted. They added that this type of bowl-like sundial is known as a hemicyclium, and was common during the Roman period.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Telling inscription

An examination of the sundial might have ended there if it weren't for an inscription on the sundial's base and bowl. On the base, researchers saw the name of "M(arcus) NOVIUS M(arci) F(ilius) TUBULA" — or Marcus Novius Tubula, son of Marcus.

Another engraving on the rim of the bowl says that Tubula (literally, "small trumpet") held the office of "TR(ibunus) PL(ebis)" — that is, plebeian tribune, and paid for the sundial "D(e) S(ua) PEC(unia)," or "with his own money."

"Not only have we been able to identify the individual who commissioned the sundial, we have also been able to determine the specific public office he held in relation to the likely date of the inscription," Launaro said.

The style of the letters allowed researchers to date the sundial to the mid-first century B.C. or onward, after the people of Interamna Lirenas had already received full Roman citizenship.

"That being the case, Marcus Novius Tubula, hailing from Interamna Lirenas, would be a hitherto unknown Plebeian Tribune of Rome," Launaro said. "The sundial would have represented his way of celebrating his election in his own hometown."

Original article on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Laura is an editor at Live Science. She edits Life's Little Mysteries and reports on general science, including archaeology and animals. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and an advanced certificate in science writing from NYU.