Tiny 'Cubesats' Gaining Bigger Role in Space

When Jordi Puig-Suari and Bob Twiggs began working on the first cubesat in 1999, their goal was a rather basic one — to develop a compact satellite that university students could build and use to conduct scientific experiments and test out new technologies.

Sixteen years later, cubesats have pushed beyond the sphere of academia, becoming major tools for governments conducting a variety of missions and for companies earning revenues from space. And, somewhat to Puig-Suari's chagrin, cubesats have begun to outgrow their original 4x4x4-inch (10x10x10 centimeters) "1U" size.

"We're starting to talk a lot about bigger things," Puig-Suari said recently. "People are talking about 6U's and 12U's and 24U's and 27U's. And I'm waiting for the day when a Hughes 702 or a Boeing 702 [communications satellite] is called a 3,045U spacecraft. Hopefully we won't get there." [Cubesats: Tiny, Versatile Spacecraft Explained (Infographic)]

Puig-Suari made these remarks in April during the 12th Annual Cubesat Developers’ Workshop in San Luis Obispo, California. The conference's subtitle was "Size Does Matter," which the California Polytechnic State University professor insisted means the opposite of its usual connotation.

"We are standardized satellites," he explained. "And, in that respect, size does matter. You don't fit the standard, you don't fly. And when you show up, they have a nice checklist, and if you're more than a millimeter off, they leave you on the ground.

"Our purpose has always been to try to be as small as possible. And there are some things we can't do small, but let's try. Let's continue to try, to push the envelope and get as small as we can," he added.

The three-day workshop was attended by a mix of academic researchers, commercial vendors, and government officials. The width and breadth of the missions discussed and the technologies involved demonstrated how far the industry has come since the first conference more than a decade ago.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Speakers at the conference laid out a series of ambitious missions that would have been unthinkable a decade earlier. Next year, for example, NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory will send two cubesats into deep space to provide real-time coverage of the entry, descent and landing of the space agency's Mars InSight lander.

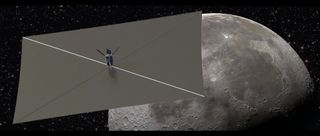

There is also The Planetary Society's LightSail spacecraft, which blasted off Wednesday (May 20) aboard the same rocket that lofted the United States Air Force's X-37B space plane. LightSail packs a 344-square-foot (32 square meters) solar sail inside a 3U cubesat, and aims to test out technologies ahead of a more involved orbital sailing trial next year.

Further, NASA's BioSentinel mission is designed to determine how much damage radiation does to DNA beyond low-Earth orbit. BioSentinel will launch in 2018 on the first flight of NASA's Space Launch System megarocket — as will fellow 6U cubesats Lunar Flashlight and Near-Earth Asteroid Scout, which will hunt for water ice on the moon and study a space rock, respectively.

Another cubesat effort, NanoSwarm, is focused on the study of particles and magnetic fields of airless planetary bodies.

Most cubesats have ridden to space as secondary payloads aboard large rockets. Conference participants heard how this situation is beginning to change as new companies begin to develop small-satellite launch vehicles.

It is quite a change from the early days, when a shortage of rides and America's strict International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) severely limited launch options.

"In 2003 [and] 2004, the idea of launching cubesats in the U.S. was insane," Puig-Suari recalled. "Literally. And we were going to launch providers, and they were saying, 'You're crazy.' And of course we said, we'll go launch in Russia. No, you can't — [there's] ITAR."

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Douglas Messier is the managing editor of Parabolicarc.com, a daily online blog founded in 2007 that covers space tourism, space commercialization, human spaceflight and planetary exploration. Douglas earned a journalism degree from Rider University in New Jersey as well as a certificate in interdisciplinary space studies from the International Space University. He also earned a master's degree in science, technology and public policy from George Washington University in Washington, D.C. You can follow Douglas's latest project on Twitter and Parabolicarc.com.

Most Popular