What Pluto Can Teach Scientists About 'Star Wars' Planet Tatooine

In recent years, planetary scientists have begun to suggest that Pluto and its moons might have something in common with the fictional planet Tatooine — the home of Luke Skywalker in the "Star Wars" movies.

Pluto and its largest moon, Charon, orbit each other in a way that is similar to binary star systems, or two stars that orbit close together. On Tatooine, this arrangement led to gorgeous dual sunsets. But how would rocky, habitable planets form in such a strange environment? Pluto and Charon might provide scientists with an answer.

"In terms of the dynamics of how planets form around binary star systems, Pluto is the closest example we have," Scott Kenyon, a theoretical astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), told Space.com. [The Pluto Flyby: Our Complete Coverage]

Plenty of Tatooines

In 1977, the movie "Star Wars" was released in theatres and featured what would eventually become one of the most iconic sunsets in movie history: a desert landscape topped by a purple and red sky featuring two glowing suns (the illusion was created by overlaying two different shots of the sun).

When young Luke Skywalker looked longingly at that beautiful skyscape, he seemed to be wondering whether he would ever leave his desert home and find adventure. It's likely that many planetary scientists had the same longing in their eyes when staring at that sunscape, wondering if they would find evidence of such planets existing in the real world.

Fifteen years later, scientists caught sight of the first evidence of planets around other stars. Today, a handful of gas giants have been spotted orbiting two suns, but no rocky, terrestrial planets that might host life as we know it.

Could rocky planets exist around binary stars, and could they support life? For that to happen, the planets would need to be able to establish stable orbits for long periods of time (a few billion years at least), giving life a chance to develop under consistent, favorable conditions. [10 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"There's a long-standing argument about how difficult it is to make planets around binary star systems," Kenyon said. "There has been a myth that binary stars exert a torque on material [around the stars] that would prevent planets from forming."

But a recent paper authored by Kenyon and his frequent collaborator, Ben Bromley, shows that this isn't the case. Their computer simulations indicate that rocky planets can form just as easily around binary stars as around single stars.

Real-world examples of planets orbiting binary stars are too far away for scientists to study in detail. That's why a binary system in our own solar system would be a helpful learning tool.

Pluto and its moon family

"It's relatively recent, connecting Pluto to binary star systems," Kenyon said "Sort of a new realization among a few of us."

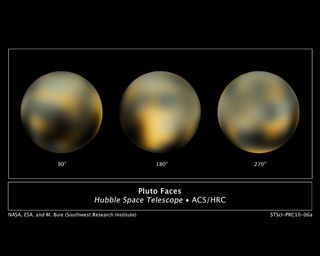

Pluto may have been stripped of its "planet" title in 2006, but it is still referred to as a "binary planet" because of its unusual orbit with Charon, which is half as wide as Pluto itself: The two bodies orbit around a point that lies between them. (Most planets are much larger than their moons, so this point lies inside the planet, often very close to its center.)

In this way, Pluto and Charon are more like a binary star system than most moon-planet systems.

"We are trying to make the connection between how planetary systems formed and how the pieces of the Pluto system formed," Kenyon said.

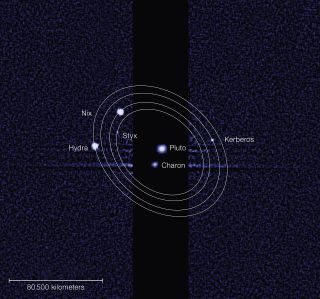

The "pieces" are Pluto's four smaller moons: the most distant moon, Hydra, was discovered in 2005 along with Nix. Kerberos, which lies between Nix and Hydra, was discovered in 2011. Styx, the inner-most moon, which is thought to be less than 15 miles (24 kilometers) across, was discovered in 2012.

If early Charon and early Pluto collided, some debris would remain in orbit, but some would be ejected. Pluto's four moon siblings live in an extremely tight orbit around their parent bodies, and Kenyon noted in a recent article in the journal Nature that how such tightly packed systems form is "an open question."

Insight into the formation of the Pluto family might come from science data taken by the New Horizons probe, which is only a few days away from its close encounter with Pluto. A close view of the shape of the moons could help scientists determine exactly how they formed.

"The question is, did the satellites form in a disk of material, or are they just fragments?" Kenyon said. "It could be a little bit of both. All four of them could be fragments, and then you would expect them to have jagged edges. Or they could have formed by aggregating fragments of a collision — like dust bunnies under your bed." (The latter case would make the satellites more round, Kenyon added).

When New Horizons flies by Pluto next week, it should give scientists a better look at the shape of the four satellites.

"The Pluto system doesn't tell us much about how Earth and Venus formed," Kenyon said. "But if we do discover Tatooines — Earth-like terrestrial planets around binary stars — then Pluto will help us understand those."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter