In 1925, Observers Lined Manhattan to Measure the Total Solar Eclipse

During a 1925 total solar eclipse over New York City, the streetlights turned on, three women fainted, vendors sold smoked glass while exhorting passersby to "save your eyes for 10 cents" and seagulls landed in the water, assuming it was night.

Twenty-five planes took airborne measurements, an airship sailed 8,000 feet (2,400 meters) above Long Island to view the event and 149 observers staked out Upper Manhattan block by block to determine the sun's precise southern limit.

Also, the eclipse came later than expected — which made the front page of The New York Times. [Here Are the Most Spectacular Solar Eclipses in US History]

During that solar eclipse, which crossed Manhattan just above 96th Street on Jan. 24, 1925 as temperatures hovered around 9 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 12.8 degrees Celsius), researchers went all out to measure the celestial event.

Today, we know the moon's precise contours and orbit, and can accurately predict an eclipse's timing and its path down to the scale of a city block. But at the time, measuring the eclipse shadow's movement across the Earth was a key opportunity to pinpoint the moon's size, shape and orbital path.

"Thousands and thousands of telescopes, spyglasses, and still and motion picture cameras were leveled at the orb," a New York Times article the next day read. "The eastern slopes of favorably situated hills were dotted with camera tripods. Opera glasses and eyepieces of every sort went up to the eyes of the parties which had gathered among the thickets of radio masts on every roof in the path of the eclipse."

"The moon was unpunctual, as well as careless of its route," the Times article added. "It was about four seconds late in blotting out the sun."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

An electric effort

A massive study undertaken by New York's electric companies was responsible for 149 of those observers, dwarfing previous measurement efforts for scale, according to eclipse researcher David Dunham.

"In 1878, there were expeditions from the U.S. Naval Observatory for a total eclipse that passed over Texas, Wyoming and Colorado," Dunham told Space.com. "They had two expeditions with observers at the predicted limits. But they were both clouded out, so they didn't get any information. They did ask citizens around Texas and Colorado to make observations and report back to them, and they actually got some observations from that effort … but it was much less than the many dozens of people that were involved with the New York City effort.

"There were a few other past efforts which also had problems, mainly due to weather — so there just wasn't anything on the scale of what was done in 1925," he added. Dunham founded the International Occultation Timing Organization in 1975 to take observations when objects pass in front of the sun and other stars, and he has also plumbed previous eclipse measurements to analyze the size of the sun over time.

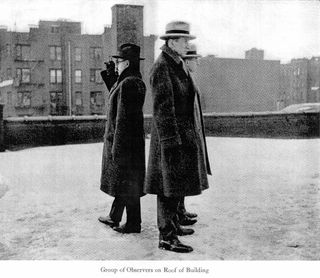

The New York observers were split into groups of two and three, and were stationed along rooftops spanning 72nd Street to 135th Street on Manhattan's West Side. At least one person would watch for the moon's incoming shadow, and another would look for whether the sun was completely covered by the moon, according to a report put out by the city's electric companies.

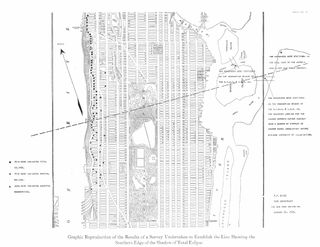

The shadow watchers were unable to provide useful data; the shadow travels at an average of 2,300 mph (3,700 km/h), so its approach is very fast and hard to quantify. But the sun observers provided good results. Everyone above 96th Street saw totality — when the moon completely covers the disk of the sun — and everyone below did not. Thus, the eclipse's southern border could be pinpointed to within 225 feet (69 m) — the distance between 230 Riverside Drive and 240 Riverside Drive, on New York City's Upper West Side. In other words, they caught the shadow's border between two buildings, each on a different city block.

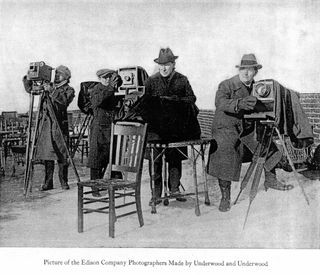

The electric companies, led by the New York Edison Company, also took detailed measurements of how much electrical power people used during the eclipse. Predictably, power use rose when it was dark, but the overall load was lower in some places because industries were closed for the morning. New York Edison Company also stationed 14 photographers throughout the city to document totality. [What Scientists Have Learned from Total Solar Eclipses]

"Flying observatories"

In addition, 50 people from the Army Air Service — a predecessor to the Air Force — flew in 25 planes to observe the eclipse. The service planned to send more, but some engines wouldn't start in the cold, according to a New York Times reporter.

And unlike the observers perched atop buildings, these air travelers got a clear view of the moon's rushing shadow:

"Observers [in the planes] saw the rush of the moon's shadow devouring the microscopic detail of the land below at the rate of a hundred square miles per second," the Times reporter wrote. "When the swarm of flying observatories alighted at Mitchel field after it was all over, their staffs reported that nothing in the whole spectacle was so impressive as the sight of the murky monster eating up white landscapes with such frightful haste."

Astronomers from the U.S. Naval Observatory also got a lofty view: They tracked the eclipse from nearly a mile in the air on the Navy dirigible dubbed Los Angeles, which lifted off from New Jersey and observed from Long Island. The researchers wielded four astronomical cameras, two motion picture cameras and a spectrograph, to measure the wavelengths of light emitted by the sun's corona.

Watson Davis, an editor for the nonprofit communications initiative Science Service, radioed down a description of the airship's view after some transmission interference.

"During the two minutes, four and six-tenths seconds of totality, not a cloud marred the magnificent spectacle of a sun so completely blotted out by the moon that the coronal fringe of the light and the ghostly radiance of the eclipsed sun turned the ocean horizon and the clouds below into a vivid picture in yellows, purples and grays, while observers drew pictures of the corona for science," Davis said, according to the New York Times.

Everyone else

An article in Popular Astronomy from the time, written by the magazine's editor, H.C. Wilson, warned that professional astronomers would be congregating near established observatories in New York and Connecticut, and that it would be "important therefore that amateurs all along the path of the total eclipse should do all that they can to obtain records of the phenomena of the eclipse" in the event that bad winter weather clouded the observatories' views.

Wilson said amateurs could time the eclipse's phases; photograph the corona and measure its spectrum; observe its effect on magnetic and wireless instruments; observe the shadow bands created; and even take "moving pictures" of the celestial event, among other suggestions.

Scientific American implored amateur astronomers and schoolchildren by radio to fill out questionnaires to describe what they saw, Marcel Chotkowski LaFollette wrote in an article for Smithsonian Institution Archives.

The final tally

All told, the many New York eyes on the eclipse found that it came a bit later than expected, and that its path was a bit farther north than scientists had predicted, thus teaching researchers more about how the moon moves around the Earth.

The careful observation of the moon's shadow "will make more precise computations possible next time," a New York Times reporter wrote.

Now, scientists know the moon's path and contours with incredible precision, as well as the Earth's exact elevation at different locations, which let researchers predict precise eclipse paths. But there is still a lot to learn about the sun's size and mechanisms of its outer atmosphere, called the corona.

The total solar eclipse on Aug. 21, 2017, could be the most watched solar eclipse in history as it crosses the continental United States from coast to coast, according to NASA, and it will provide an unparalleled research opportunity, and a chance for amateurs and professionals to collaborate. Projects such as the University of California and Google's Eclipse Megamovie project and an initiative by the International Occultation Timing Organization call for volunteers across the country to document the precise location of the moon's shadow.

New York City won't see a total solar eclipse this time around; only part of the sun's disk will be covered. But people across the country will again turn their (protected) eyes and instruments to the sun — and this time, there will be many more cameras and phones at the ready.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.