NASA Spacecraft Finds Bounty of Alien Planets, Including 104 Potentially Habitable Worlds

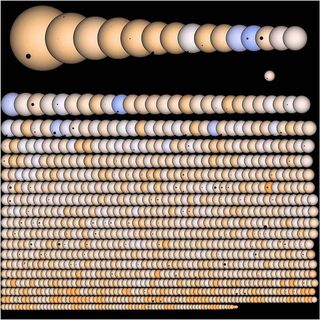

The search for other Earth-like planets in the galaxy got a major boost today (Nov. 4) with the discovery of hundreds of newfound alien planets identified by NASA's Kepler spacecraft, a haul that includes 104 strange, new worlds that could potentially support life.

Scientists with NASA's planet-hunting Kepler mission announced the discovery of 833 new planet candidates during a press conference today, bringing the total number of candidate worlds to 3,538. Of the 104 planets in the habitable zone, 10 of them are about the size of Earth, scientists say.

"We're opening a new era of exploration of our galaxy," said William Borucki, Kepler science principal investigator at NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., where scientists are discussing the latest exoplanet discoveries during the second Kepler Science Conference this week. [7 Ways to Discover Alien Planets]

The new planet count expands the number of worlds Kepler has identified by 29 percent since the last update in January, representing a 78 percent increase in the number of Earth-size planets.

The mission of the Kepler spacecraft, launched in 2009, is to determine what fraction of stars in the Milky Way harbor Earth-size planets orbiting in the habitable zone. As of today, scientists are on the brink of answering that question.

The Kepler telescope spent the past four years staring at a patch of sky in the constellation Cygnus, looking for minuscule dips in the brightness of stars that signify a planet crossing in front of, or transiting, their star.

The search has turned up a cornucopia of bizarre worlds, including "hot Jupiters" that orbit very close to their host stars; icy Neptune-like worlds; and large rocky "super-Earths."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Scientists announced the first confirmed planet in a habitable zone, Kepler 22-b, at the first Kepler Science Conference two years ago. Research now suggests that most stars in the galaxy have at least one planet.

Kepler stopped taking data May 11, when it suffered a failure of the second of four reaction wheels used to point the spacecraft. But Kepler hasn't quit kicking yet. Scientists will continue to mine the vast stores of Kepler's star brightness data — freely available online — to look for new planets.

"There's a full year of data yet to be analyzed," Borucki said, adding that he expects scientists will find more of the smallest planets at longer Earth-like orbits.

An independent analysis of Kepler's data found that one in five sunlike stars harbors an Earth-size planet in the habitable zone.

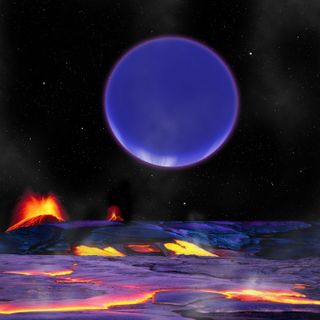

Just last week, scientists announced the discovery of the first Earth-size rocky planet, Kepler-78b. However, the planet, which whips around its star once every 8.5 hours, has a blazing surface temperature of about 3,680 degrees Fahrenheit (2,027 degrees Celsius) — far too hot for life as we know it.

Other rocky planets found by Kepler include Kepler-10b and Kepler-36b.

No true Earth analogues — Earth-size planets with Earth-length years in the habitable zone around sunlike stars — have yet been found, but Kepler scientists are optimistic.

"The trend of finding Earth-like planets is likely to continue," said research scientist Jason Rowe of the SETI Institute, in Mountain View, Calif.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.