On Saturn's Moon Titan, Methane Rain Transforms Into Icy Reservoirs

Compounds in the icy crust of Saturn's moon Titan may be slowly changing the composition of the liquid methane lakes and seas at its surface.

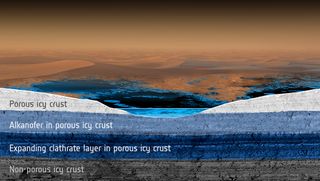

According to a new study, crystal structures in the icy crust of Titan could mix with liquid from underground reservoirs, changing the makeup of the bodies of liquid created by hydrocarbon rainfall. The shifting composition could allow scientists to understand more about processes going on deep underground by studying the surface.

"We knew that a significant fraction of the lakes on Titan's surface might possibly be connected with hidden bodies of liquid beneath Titan's crust, but we just didn't know how they would interact," lead author of the study Oliver Mousis, of the University of Franche-Comte in France, said in a statement. "Now, we have a better idea of what these hidden lakes or oceans could be like." [See amazing photos of Titan]

Titan's crystal traps

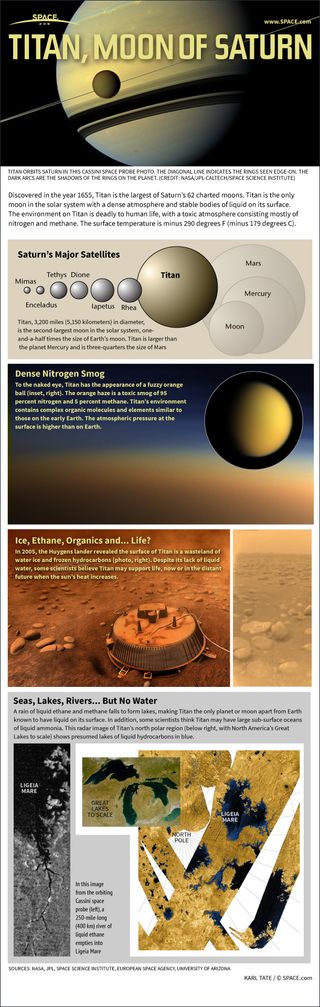

Not long after it reached Saturn in 2004, NASA and the European Space Agency's Cassini spacecraftspotted the first of the known lakes and seas on the planet's large moon Titan. Instead of water, these bodies of liquid are filled with organic compounds known as hydrocarbons, which include methane.

Other reservoirs are thought to house icy material beneath the surface. Most of the hundreds of lakes and seas known today are found in the moon's north polar region.

Rainfall from clouds in Titan's atmosphere seems to feed the lakes and seas, but scientists aren't certain how the liquids move through the crust and atmosphere.

Working with colleagues from Cornell University in New York and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, Mousis modeled how liquid hydrocarbons in a reservoir beneath the surface might spread through the moon's icy crust. They determined that the formation of materials known as clathrates could change the composition of the rainfall runoffs that charge the reservoirs.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Crystal-like structures with small cages that trap other molecules, clathrates on Titan form as liquid hydrocarbons come into contact with the water ice that dominates the moon's crust. On Earth, clathrites are found in some polar and ocean sediments, often capturing frozen methane. On Titan, the lattice-like clathrates could capture substances such as methane and ethane, and should remain stable up to several miles beneath the moon's surface.

Hidden reservoirs on Titan

At the bottom of Titan's reservoirs, the liquid hydrocarbons would interact with clathrates, trapping and splitting molecules into a mix of liquid and solid phases. As material from the subsurface reservoir diffused through the icy crust, a second body would form beneath it, from clathrates and stretching down to where denser ice became less porous.

The new reservoir interacts with its parent reservoir above, slowly changing its composition. Eventually, the original methane reservoir would become dominated by propane or ethane.

"Our study shows that the composition of Titan's underground liquid reservoirs can change significantly through their interaction with the icy subsurface, provided the reservoirs are cut off from the atmosphere for some period of time," co-author Mathieu Choukroun of JPL said in the same statement.

These changes would be detectable from the surface. Lakes and rivers fed by springs from propane or ethane reservoirs would show the same composition. Those dominated by rainfall would contain a significant fraction of methane. Studying the liquid at the surface could reveal a great deal about processes occurring miles underground.

The new findings are published in the September 1 issue of the journal Icarus.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebookand Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd

Most Popular