Mercury Transit 2019: Here Are the Stages to Watch

Skywatchers must use special sun-viewing lenses to safely observe Mercury's transit.

A simple journey can take many steps, and on Monday (Nov. 11), skywatchers can view several stages of the journey of the smallest planet in the solar system when it passes in front of the sun.

People in the United States and other parts of the world will be able to catch Mercury’s roughly 5.5-hour trip across the solar disk. This event, also known as a transit, will be livestreamed by several platforms and featured in many local events. Please keep in mind to always use ISO-certified protection when looking directly at the sun.

One fantastic way to safely observe this rare event — which won't be seen again from the U.S. until 2049 — comes via NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) website. A team of scientists, engineers and web programmers from the mission will be on deck to regularly update the site with the latest up-close sights. Websites like Slooh and timeanddate.com will also host livestreams.

Related: Mercury Transit 2019: Where and How to See It on Nov. 11

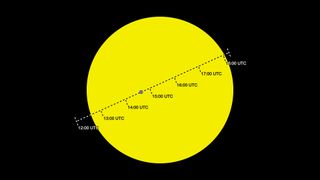

First contact (7:35 a.m. EST, 12:35 GMT)

The transit will begin to be visible to people on Earth at first contact, when the planet's disk is externally tangent to the sun. This will happen slightly past sunrise on the U.S. East Coast at 7:35 a.m. EST (1235 GMT). The sun will, however, sit below the horizon for those watching from the West Coast, making this bit of the event invisible to those observers.

Second contact (7:37 a.m. EST, 1237 GMT)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Mercury reaches second contact when its entire shadow appears as a small but complete silhouette on the solar disk. This happens a couple of minutes later, at 7:37 a.m. EST (1237 GMT), at the moment when Mercury's trailing limb lines up with the sun's edge. At this point during the transit, look for what's called the "black drop effect" — a black teardrop shape that appears to connect Mercury to the edge of the solar disk. This is an illusion caused by imperfections in telescope optics.

Third contact (1:02 p.m. EST, 1802 GMT)

If you missed the black drop effect during the second contact, you have one more chance to see it — only this time it will be a mirror image. This point in the transit is called third contact, and it happens several hours after second contact, at 1:02 p.m. EST (1802 GMT). Here, Mercury reaches the other end of the solar disk and appears whole for the last time.

Transit ends (1:04 p.m. EST, 1804 GMT)

Fourth contact wraps up the event visible on Earth, when Mercury's shape moves out of the solar disk and touches it for the last time. This occurs at 1:04 p.m. EST (1804 GMT).

For more detailed information about Mercury's transit, skywatchers can also check out the work of Fred Espenak, aka Mr. Eclipse, who runs the skywatching website eclipsewise.com.

Editor's Note: Visit Space.com on Nov. 11 to see live webcast views of the rare Mercury transit as shown from telescopes on Earth and in space, along with complete coverage of the celestial event. If you SAFELY capture a photo of the transit of Mercury and would like to share it with Space.com and our news partners for a story or gallery, you can send images and comments in to spacephotos@space.com.

- Mercury Transit 2019: How to Find an Event Near You

- Shallow Craters on Moon and Mercury May Hide Thick Slabs of Water Ice

- BepiColombo Spacecraft Snaps Selfies En Route to Mercury

Follow Doris Elin Urrutia on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.