Future Mars Rover May Use Bigger Parachute and Atomic Clocks

FARNBOROUGH, England — A possible rover mission to Mars within the next eight years may rely on a larger parachutes, atomic clocks and inflatable decelerators, NASA's Mars exploration chief says.

With a large NASA rover only weeks away from arriving at the Red Planet, NASA's Doug McCuistion outlined ideas for another, far less expensive Martian mission in 2018 or 2020.

The inflatable decelerators, also known as ballutes, and big parachutes would help the spacecraft reduce its speed through the Martian atmosphere, while the atomic clocks would improve its landing accuracy, McCuistion announced Tuesday (July 10) at the Farnborough International Airshow here.

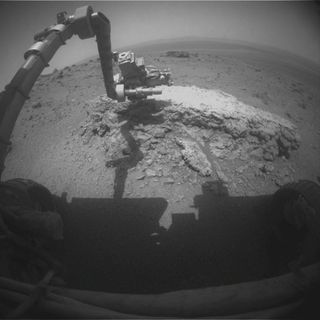

NASA expects to have up to $800 million to spend on the mission. That's a far cry from the $2.5 billion the agency is spending on its 1-ton Curiosity rover, which is due to land on the Red Planet Aug. 5.

"That price point [$800 million] is frankly around the point of a Discovery mission," McCuistion told SPACE.com. "Those missions tend to be characterized by simple systems, not too challenging." [The Best (And Worst) Mars Landings in History]

McCuisition added that he likely won’t have the budget to fund the ballutes, parachutes and atomic clocks. Instead, NASA’s Office of the Chief Technologist probably would pay for them.

For its Mars missions NASA is still using parachutes based on the design of the 1970s Viking landers. Those old-school chutes are 69 feet (21 meters) wide; the 2018 or 2020 mission would employ a 98-foot-wide (30 m) chute with a design that produces far more drag.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Working within the budget

The lower price tag for a 2018 or 2020 mission reflects NASA's efforts to find a way forward in tough fiscal times. President Barack Obama's proposed 2013 federal budget, which was released in February, slashes NASA planetary science funding by 20 percent, with much of that coming out of the Mars program.

The cuts led NASA to withdraw from the European Space Agency-led ExoMars mission, which aims to send an orbiter and rover to the Red Planet in 2016 and 2018, respectively.

In response to its new budget situation, NASA asked scientists for ideas on how to explore Mars on the cheap. The most promising of these proposals were presented at a workshop at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston in late June.

The workshop’s final report, with recommendations, is to be delivered to NASA by the end of August. However, the report summarizing the workshop’s findings is now available on the LPI website.

The report describes several possible scenarios for a 2018 or 2020 mission, including a lander or a rover similar to the twins Spirit and Opportunity, which landed on Mars in January 2004 and exceeded all mission expectations.

The summary also states that workshop participants saw value in early international involvement in whatever mission is chosen. They also expected that technology advances will deliver instruments that can meet scientists' goals while on the sort of rover or fixed station that NASA has already sent to the Red Planet.

McCuistion will use the workshop's final report in his 2014 budget submission, which he will deliver to the administration later this year.

Planning for 2018 (or 2020)

NASA has yet to decide if it will send a rover, lander or orbiter to Mars later this decade, and its decision will be guided by its long-term goals of a Martian sample-return mission and a human flight to the Red Planet, officials have said.

NASA’s next Mars mission, MAVEN (for Mars Atmosphere Volatile Evolution), involves an atmosphere-analyzing orbiter slated to arrive in 2015. If the 2018 or 2020 mission is another orbiter, it could use new laser communications systems.

Curiosity is to be lowered to the Martian surface on cables by a rocket-powered sky crane. Such a system could be used to enable human missions to the Red Planet, McCuistion said.

A sky crane in combination with a surface beacon could deliver 2,200 pounds (1,100 kilograms) of cargo to within a few hundred yards of a target location, he said.

Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rob Coppinger is a veteran aerospace writer whose work has appeared in Flight International, on the BBC, in The Engineer, Live Science, the Aviation Week Network and other publications. He has covered a wide range of subjects from aviation and aerospace technology to space exploration, information technology and engineering. In September 2021, Rob became the editor of SpaceFlight Magazine, a publication by the British Interplanetary Society. He is based in France. You can follow Rob's latest space project via Twitter.