Scientists to Discuss Universe's Strange Dense Spot Wednesday: Watch Live

An odd dense spot in the universe populated by a surprising amount of matter has been puzzling scientists since it was revealed in March in an all-sky map made by the European Planck satellite. This feature and other mysteries in the observations may point the way toward new theories of physics, say scientists who met recently to discuss the implications of the findings.

Three Planck team members will answer public questions about the Planck data during a Google+ Hangout on Wednesday (July 31) at 3 p.m. EDT (1900 GMT), sponsored by the Kavli Foundation. You can watch the Hangout live here on SPACE.com. Questions for the researchers can be submitted in advance by emailing info@kavlifoundation.org or posting on Twitter with hashtag #KavliAstro.

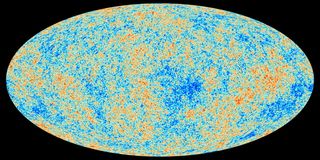

Planck measures ancient light pervading the universe called the cosmic microwave background (CMB), which dates from just a few hundred thousand years old. This light records a record of what the universe like shortly after its birth in the Big Bang, and thus offers a test of theories of how the cosmos came to be. [Gallery: Planck Spacecraft Sees Big Bang Relics]

Ultimately, the spread of matter throughout space is thought to be due to slight variations in the energy density of the young universe that are evident as temperature variations in the cosmic microwave background light. Mostly, these density variations are evenly spread throughout the sky, but one anomalous spot is particularly dense, which shows up in the data as a particularly cold area.

"[T]his is very strange," George Efstathiou, a professor of astrophysics at the U.K.'s University of Cambridge and director of the Kavli Institute for Cosmology at Cambridge, said in a statement. "And I think that if there really is anything to this, you have to question how that fits in with inflation … It’s really puzzling."

Inflation is a leading theory suggesting that within the first fraction of a second after the Big Bang, the universe grew exponentially in size.

"[T]he theory of inflation predicts that today’s universe should appear uniform at the largest scales in all directions," Efstathiou said. "That uniformity should also characterize the distribution of fluctuations at the largest scales within the CMB. But these anomalies, which Planck confirmed, such as the cold spot, suggest that this isn’t the case."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

By investigating the cold spot and other mysteries in the CMB, physicists hope to discriminate between different versions of inflation theory, and perhaps open the door to further theories.

"Perhaps we may still eliminate these anomalies with more precise analysis; on the other hand, they may open the door to something much more grand — a reinvestigation of how the whole structure of the universe should be," Krzysztof Gorski, a Planck Collaboration scientist and senior research scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement.

You can also watch Wednesday's Planck webcast directly at the Kavli website here.

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.