Our Universe: It's the 'Simplest' Thing We Know

Our universe is actually really simple, it's just our cosmological theories that are getting needlessly complex, argues one of the world's leading theoretical physicists.

This conclusion may sound counterintuitive; after all, to fully understand the true complexities of Nature, you need to think bigger, study things on finer and finer scales, add new variables to equations, and think up "new" and "exotic" physics. Eventually we'll discover what dark matter is; eventually we'll gain a grasp of where those gravitational waves are hiding – if only our theoretical models were more advanced and more... complex.

Not so, says Neil Turok, Director of the Perimeter Institute of Theoretical Physics in Ontario, Canada. By Turok's rationale, if anything, the universe, on its largest and smallest scales, is telling us that it is actually amazingly simple. But to fully grasp what this means, we'll need a revolution in physics.

PHOTOS: Cosmos Snaps Into Dazzling Focus With Hubble Upgrade

In an interview with Discovery News, Turok pointed out that the biggest discoveries of the last few decades have confirmed the structure of the universe on cosmological and quantum scales.

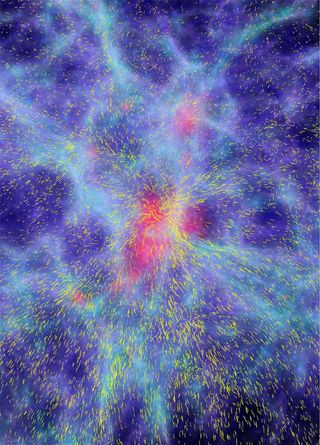

"On the largest scales, we've mapped the whole sky -- the cosmic microwave background -- and measured the evolution of the universe, the way it's changing, the way it's expanding ... and these discoveries reveal that the universe is astonishingly simple," he said. "In other words you can describe the structure of the universe, its geometry, and the density of matter ... you can essentially describe all that with just one number."

The most fascinating outcome of this reasoning is that to describe the universe's geometry with one number, it is actually simpler than the numerical description of the simplest atom we know -- the hydrogen atom. The hydrogen atom's geometry is described by 3 numbers, which arise from the quantum characteristics of an electron in orbit around a proton.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It basically tells us that the universe is smooth but it has a small level of fluctuation, which this number describes. And that's it. The universe is the simplest thing we know."

At the opposite end of the scale, a similar thing happened when physicists probed into the Higgs field, using the most complex machine ever constructed by humankind, the Large Hadron Collider. When, in 2012, physicists made the historic discovery of the particle that mediates the Higgs field, the Higgs boson, it turned out to be the simplest type of Higgs described by the Standard Model of physics.

"Nature has gotten away with the minimal solution, the minimal mechanism you could imagine to give particles their mass, their electric charges and so on and so forth," said Turok.

OPINION: Will Gravitational Waves Ever Be Found?

Physics from the 20th century has taught us that as you gain more precision and you probe deeper into the quantum realm, you discover a zoo of new particles. So as the experimental results generated a bounty of quantum information, theoretical models predicted more and more outlandish particles and forces. But now we're reaching a crossroads where many of our most advanced theoretical ideas about what lies "beyond" our current understanding of physics are turning up few experimental results that support their predictions.

"We're in this bizarre situation where the universe is talking to us; it's telling us that it's extremely simple. At the same time, the theories that have been popular (from the last 100 years of physics) have become more and more complicated and arbitrary and un-predictive," he said.

Turok pointed to String Theory that was billed as the "final unified theory," wrapping all of the universe's mysteries up in a neat package. Also, the search for evidence of inflation -- the rapid expansion of the universe just after the Big Bang nearly 14 billion years ago -- in the form of primordial gravitational waves etched into the cosmic microwave background (CMB), or the "echo" of the Big Bang. But as we seek out experimental evidence, we're left clutching at proverbial straws; the experimental evidence simply is not agreeing with our maddeningly complex theories.

Our Cosmic Origins

Turok's theoretical work focuses around the origins of the universe, a subject that has garnered a lot of attention in recent months.

Last year, the BICEP2 collaboration, which uses a telescope located at the South Pole to study the CMB, announced the discovery of primordial gravitational wave signals in the Big Bang's echo. This is basically the "Holy Grail" of cosmology -- the discovery of gravitational waves that were spawned by the Big Bang would confirm certain inflationary theories of the universe. But unfortunately, for the BICEP2 team, they announced the "discovery" prematurely and the European Planck space telescope (that is also mapping the CMB) revealed that the BICEP2 signal was caused by dust in our galaxy and not ancient gravitational waves.

ANALYSIS: BICEP2 Gravitational Wave 'Discovery' Deflates

What if these primordial gravitational waves are never found? Many theorists who have pinned their hopes on the Big Bang followed by a rapid period of inflation may be disappointed, but according to Turok, "it will be a very powerful clue" that the Big Bang (in a classical sense) may not be the absolute beginning of the universe.

"The biggest challenge for me has been to describe the Big Bang itself, mathematically," Turok added.

Perhaps a cyclical model for universal evolution -- where our universe collapses and rebounds anew -- may better fit the observations. These models do not necessarily generate primordial gravitational waves and if these waves are not detected, perhaps our inflationary theories need to be thrown out or modified.

As for the gravitational waves that are predicted to be generated by the rapid motion of massive objects in our modern universe, Turok is confident that we are reaching a realm of sensitivity that our gravitational wave detectors will detect them very soon, confirming another one Einstein's space-time predictions. "We do expect to see the gravitational waves from black hole collisions within the next 5 years," he said.

The Next Revolution?

From the largest scales to the smallest scales, the universe seems to be "scale-free" -- in other words, no matter what spatial or energy scale you look at, no scale is "special." And this finding actually suggests the universe has a far simpler nature than current theories suggest.

"Yes, it's a crisis, but it's a crisis of the best kind," said Turok.

ANALYSIS: Planck's Mystery Cosmic 'Cold Spot' Could be an Error

So, to explain the origins of the universe and come to terms with some of our universe's most perplexing mysteries such as dark matter and dark energy, we may need to look at our cosmos differently. But this will require a revolution in physics understanding, a revolution possibly as historic as Einstein's realization that space and time are one of the same thing when he formulated his theory of general relativity 100 years ago.

"We need a very different view of basic physics. This is the time for radical, new ideas," he concluded, pointing out that this is a great time in human history for young people to get into the field of theoretical physics, as it will be the next generation that will likely transform the way we view the universe.

To find out more about Turok's research and the apparent simplicity of the universe, tune into his Perimeter Institute public lecture at 7pm ET today (Wednesday). The lecture will be streamed LIVE on Discovery News.

Originally published on Discovery News.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Ian O'Neill is a media relations specialist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California. Prior to joining JPL, he served as editor for the Astronomical Society of the Pacific‘s Mercury magazine and Mercury Online and contributed articles to a number of other publications, including Space.com, Space.com, Live Science, HISTORY.com, Scientific American. Ian holds a Ph.D in solar physics and a master's degree in planetary and space physics.