They're Full of Stars! Students Find Densest Galaxies in the Universe

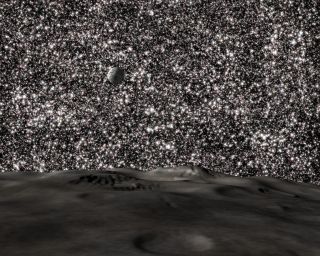

Talk about a starry night: A pair of university students in San Jose has found what appear to be the densest galaxies ever seen — cosmic realms where the night sky would appear ablaze with stars from the surface of a planet.

The students, Richard Vo and Michael Sandoval, discovered the so-called ultracompact dwarf galaxies while sifting through open-source archives of astronomy observations by several different observatories as undergraduates at San Jose State University in California. They also created a video simulation depicting how such dense galaxies can form with a supermassive black hole at their core.

Looking up from a planet embedded inside one of the newfound galaxies, an observer would see more than a million stars at once, compared to the few thousand stars visible in Earth's night sky, researchers explained. But the way these ultradense star clusters form, and whether they are actually galaxies at all, is still unknown.

"People have written sci-fi stories about things like this; it's nice to see one that actually exists," said Aaron Romanowsky, an astronomer at San Jose State University who served as the students' adviser and co-author of the new study.

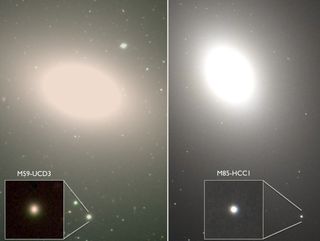

The first known ultracompact dwarf galaxy was found in 2013, surprising astronomers by having a supermassive black hole at its heart despite its small size. But the two newly discovered objects are even more tightly packed with stars. The first new object is about twice as dense as the original find, and the second object is a whopping 200 times denser than the original.

Something new

"This class of object was overlooked for a hundred years," Romanowsky told Space.com. "It's such a bright object, easy to see, but people didn't know to look at it." Romanowsky was also part of the team that found the first ultracompact dwarf galaxy two years ago. [A Tiny Dwarf Galaxy and Its Giant Black Hole (Video)]

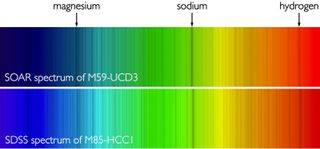

In the past, such star clusters would have been mistaken for foreground stars because of their brightness. But when these clusters are examined more closely, the single point of light resolves into a fuzzy cluster, and spectrum data reveal it's much farther away.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The width of one of the ultracompact dwarf galaxies, called M59-UCD3, is 200 times smaller than that of the Milky Way galaxy, but its star density is about 10,000 times higher. The other newfound galaxy, called M85-HCC1, has even more stars — its stellar density is 1 million times that of the Milky Way, and even led researchers to coin a new phrase for it: hypercompact cluster.

The students investigated data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii, the Hubble Space Telescope, and the Southern Astrophysical Research Telescope in Chile. Although they intended to survey about one-third of the sky, each of them happened to discover an ultradense object not long after they began searching.

"It was a training procedure, actually," said Vo, who is now a graduate student at San Francisco University in California. "He [Romanowsky] said, 'There's an ultracompact dwarf here; I want you to find it for yourself,'" Vo told Space.com.

But, in addition to the dwarf, he noticed another mysterious cluster. "And it ends up being one of the densest objects in the sky we have discovered so far," Vo said.

The research is detailed in the July 20 edition of The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Telltale signs

Ultracompact dwarf galaxies have perplexed astronomers because they seem to defy classification. They're too tiny to clearly be galaxies, but far too dense to be ordinary clusters of stars. [A Zoo of Galaxies in Infrared (Images)]

"For decades, a hundred years, there was a pretty clear distinction — how do you know the difference between a human and an elephant?" Romanowsky said. "Now, we're finding things that are halfway in between, and we don't know what to call them … The word we use is 'ultracompact dwarf,' but it's an intentionally ambiguous word."

The first ultracompact dwarf — which previously held the title of densest galaxy — puzzled astronomers until they spotted a supermassive black hole at its core. That detail suggested that it might have been a large galaxy at some point, before losing most of its stars. Researchers suspect that close interaction with another galaxy, whose gravity stripped off stars as they passed one another, might have transformed a normal dwarf galaxy into a dense ultracompact dwarf.

Sandoval, now a graduate student at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, put together the above video simulation to demonstrate that process.

"We all know, from a mechanics/theory perspective, how things interact in space, [but] it is still hard to visualize how it actually looks in physical space," Sandoval told Space.com in an email. "My goal was to see how the theory of tidal stripping would look in physical space, to accurately represent it, and to hopefully start up a method of analyzing phenomena that we can't actually 'see' happening with our own eyes."

The simulation was about as accurate as Sandoval could get without a supercomputer, and it incorporated imagery others had created showing what it would be like to look around inside the system, he said.

Going forward, the researchers will be searching for telltale signs of this process happening in the newly discovered objects; they'll look for a supermassive black hole in the center and further analyze disturbances in the "host" galaxies near the objects. Those disturbances suggest that the large galaxies recently consumed stars from the ultracompact dwarfs; heavy metals in the dwarfs also suggest their previous size, as heavy metals are often synthesized by larger galaxies.

Romanowsky said that understanding how these objects form will teach astronomers about the formation of modern galaxies and what happens when they go head-to-head.

"In astronomy, there's so many discoveries still to be made," he added. "We're still in the exploration phase, and even undergraduates can still make discoveries."

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.

Most Popular