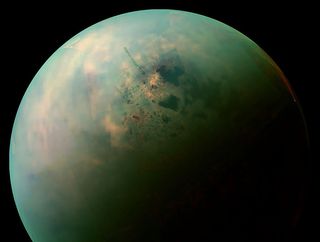

Mysterious 'Bathtub Rings' of Titan Replicated on Earth

Something dark is spreading across the surface of Titan, and we may finally have some idea what it is.

Titan, Saturn's largest moon, is the only other object in our solar system (besides Earth) known to have liquid on its surface. Frigid seas of methane and ethane fill depressions on the moon like water fills in lakes and oceans on Earth. In regions near Titan's equator where those liquids have evaporated, researchers have spotted dark smears. Without a close-up view of those smears, however, it's difficult to know what they're made of. But researchers suspect the features function a great deal like rings in a bathtub, where solids that were once dissolved in a liquid are left behind as that liquid evaporates. Now, there's a new piece of evidence bolstering this theory.

A team of researchers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) dumped methane, ethane and other carbon-containing molecules into a chamber that was chilled to temperatures similar to those on Titan and that was filled with a similar atmosphere. [In Photos: A Look at Titan's Bizarre Seas]

When bathtub ring-style formations happen on Earth, they result from solids "dropping out" of a liquid as it evaporates. In this chamber, the first solids to drop out, according to a statement, were benzyne crystals. Benzyne is a common enough molecule on Earth, present in gasoline, but in this supercooled chamber, the substance's hexagonal molecules wrapped themselves around ethane molecules and formed crystals.

Next to drop out were crystals that included acetylene and butane, two more hydrocarbons. Based on what's known about Titan's composition, this acetylene-butane crystal is probably much more common on Titan, the researchers said in their statement.

This experiment demonstrates that under Titan-like conditions, bathtub rings of hydrocarbon crystals can form. That doesn't mean those crystals are forming similar rings on Titan, however. [Amazing Photos: Titan, Saturn's Largest Moon]

"We don't know yet if we have these bathtub rings [on Titan]," Morgan Cable, a researcher at JPL who led this research team, said in the statement. "It's hard to see through Titan's hazy atmosphere."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Cable, who will present the results today (June 24) at the 2019 Astrobiology Science Conference in Bellevue, Washington, said in the statement that to know for certain, scientists will have to get a probe much closer to the lakes.

- 7 Far-Out Discoveries About the Universe's Beginnings

- The 12 Strangest Objects in the Universe

- Science Fact or Fiction? The Plausibility of 10 Sci-Fi Concepts

Originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rafi wrote for Live Science from 2017 until 2021, when he became a technical writer for IBM Quantum. He has a bachelor's degree in journalism from Northwestern University’s Medill School of journalism. You can find his past science reporting at Inverse, Business Insider and Popular Science, and his past photojournalism on the Flash90 wire service and in the pages of The Courier Post of southern New Jersey.